Flemmie Pansy Kittrell was a leader in the field of home economics, with a particular interest in the nutrition and holistic well-being of children from Black and low-income families. Born to sharecropping parents in North Carolina in 1904, Kittrell was the eighth of nine children. At just 11 years old, she started working as a cook and a maid, and she used the income to pay for her education over the years. In 1936 she became the first Black woman to earn a Ph.D. from Cornell University and the first Black woman in the country to earn a Ph.D. in nutrition.

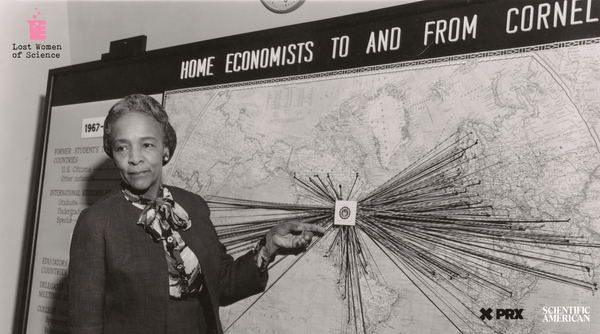

But Kittrell was interested in more than food. She wanted to know how a child’s overall environment affected their success and well-being. In the 1960s she directed an experimental nursery at the campus of Howard University. This nursery would later serve as a model for Head Start, a federal program that provides for the early education, good health and nutrition of preschool children from low-income families. Kittrell would go on to travel internationally, studying and advising on matters of children’s health and nutrition.

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

[New to this season of Lost Women of Science? Listen to the most recent episodes on Lillian Gilbreth and Lise Meitner: Episode One and Episode Two.]

Lost Women of Science is produced for the ear. Where possible, we recommend listening to the audio for the most accurate representation of what was said.

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

Carol Sutton Lewis: Hello, it’s Carol Sutton Lewis here, and today I’m joined by Danya AbdelHameid who has a story for us.

Danya Abdelhameid: Hi Carol. So I want to start by telling you about a nursery in the 1960s. It was on the campus of Howard University in Washington D.C. This nursery was inside a modernist building, with a little playground tucked away in the back.

Caffey-Flemming: Most people didn't know it was even there. You can't see it from the main part of campus.

Abdelhameid: Dolores Caffey-Flemming was a student at Howard when she was hired to work there. Her job was to plan activities for the kids each week.

Caffey-Flemming: And it was very scary for me because when I went in I didn't know what to expect. I didn't realize how much you really need to know about a child.

Abdelhameid: Like, apparently, you weren’t supposed to give them sugar. Who knew? Dolores was young and inexperienced with kids. And now she’s spending all day with two to three dozen of them, tiny ones, aged three to four years old, making sure they were cared for physically, mentally, emotionally. It felt like a big responsibility. But she quickly settled into a daily routine with the kids.

Caffey-Flemming: They would come in the morning, and they would have breakfast. Then, of course, they had a little free playtime outside. And then they would have different activities. You know, it could be a story time. It could be finger painting. Every day was a different day, a different activity.

Sutton Lewis: Yeah, that sounds like a nursery! [laughs]

Abdelhameid: But this nursery also had something else.

Caffey-Flemming: They had an observation booth with glass that you can see out and the children couldn't see you.

Abdelhameid: The woman behind this nursery school slash laboratory was a Black home economist named Flemmie Kittrell. A very prim and proper 1960s lady. Went to church every Sunday. Always wore dresses or skirts, never pants. And even though she was dedicated to free play for the kids in this nursery, Flemmie herself did not play.

Caffey-Flemming: She was very, very serious. She did not, you know, go for any foolishness.

Abdelhameid: Flemmie Kittrell was the chair of the Home Economics Department at Howard. Now, if you took home economics in school, you might just think of baking brownies and sewing pillowcases. You might not take it seriously.

But in the 1960s, Flemmie and her fellow home economists conducted groundbreaking research on one of the most important questions of the day: how do you raise a child? They insisted there was a science to something a lot of people assumed was a matter of instinct.

It was an idea that was becoming as important to policymakers as it was to parents. In the mid-1960s, President Lyndon Johnson declared a “War on Poverty.” And he argued that the cause of poverty was that people just weren’t given a fair shot—they didn’t get the medical care they needed, the education to help them succeed, and that these problems started in childhood. So that seemed like a good time to intervene. But it was an open question: If you gave a poor kid a boost early in life, would it matter later on? Home economists like Flemmie Kittrell were determined to find out.

So today, you’ll hear Flemmie’s story, a woman just two generations removed from slavery, born to a family of sharecroppers in the South, who decided to conduct a radical experiment: take a group of Black kids living in poverty and put them in a really fantastic nursery. For two years, give them good food, fun activities, and a lot of love – and see what happens. Would they do better once they went off to school? How much of a difference would it make? How much does what happens early in a kid’s life shape the rest of it?

Sutton Lewis: This is Lost Women of Science. I’m Carol Sutton Lewis, and today I’m joined by Danya AbdelHameid who brings us the story of Flemmie Kittrell.

So, Danya, I am so excited to hear this story because this is a topic so close to my heart for two reasons. First of all, I host a parenting podcast. I also am a parent and I had all three of my children in program where they were two and three years old, and they were playing in room with an observational mirror, a one way where I could look in and they couldn't see me, so I'm really excited to hear about how this all came to be and what Flemmie Kittrell learned.

Abdelhameid: I have so many questions about that, but I’ll just say the first thing is you being a parent is kind of already more experience than Flemmie herself had. She never raised kids, but like all of us, she did have some direct experience being a kid.

So Flemmie Pansy Kittrell – that was her full name – she was born in 1904 in Henderson, North Carolina, which is a small rural town near the Virginia border.

Flemmie Kittrell: Now, uh, my mother had nine children, and I was the eighth of the nine. She had four girls and five boys.

Abdelhameid: That voice is Flemmie’s on a scratchy old tape from 1977. She was interviewed just three years before she died as part of the Black Women Oral History Project at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

Sutton Lewis: Okay, wait, let me just stop right there. This explains why she didn’t have any children. She was one of nine kids. [laughs] I understand now why she had none of her own. Keep going, sorry.

Kittrell: Being the youngest, uh, almost the youngest member and the youngest, uh, girl in the family. I had the benefit of many of the privileges that my older brothers and sisters had had, uh, without having to work for them so to speak.

Abdelhameid: This is the early 1900’s and Flemmie is only two generations removed from slavery, meaning her grandparents were enslaved, and her parents were sharecroppers. They all lived in a four-room house on the lands that they farmed.

Allison Horrocks: This was not a family with a lot of resources.

Abdelhameid: Allison Horrocks is a public historian, and her Ph.D. thesis was all about Flemmie Kittrell and the history of home economics.

Horrocks: She always talked about her family really valuing education. You can say that, but to actually see her and her siblings getting this pretty big opportunity for the time period, I think really bears that out.

Abdelhameid: Flemmie and her two older siblings went to college at Hampton Institute, now known as Hampton University, a historically Black university in southeastern Virginia. And Flemmie got a scholarship and fellowships to cover some of the cost, but not all of it, so she had to work.

Horrocks: Everyone worked at Hampton. That was part of the ethic of the system.

Abdelhameid: This wasn’t new to Flemmie. She’d been working since she was 11 years old, first as a nursemaid during summer breaks, then as a cook for wealthier families.

Horrocks: And she actually does domestic service while she is a high school and college student as part of earning her keep.

Abdelhameid: When she was in high school, getting ready to go to college, Flemmie had no interest in studying home economics. It was the last thing she wanted to major in.

Kittrell: I had thought I wanted to be in political science or some field like that. And then one of my teachers, Mrs. Rollonson, um, called me in one day, just as I was about to graduate from high school, and wanted to know what had I decided to do for the future. And then she said, well, have you thought of home economics? And I said, well, I don't think I'd like that. I didn't have a good reason, except I just thought the home was just so ordinary. You know all about it anyway.

Abdelhameid: But Mrs. Rollonson doesn’t let it go – she points Flemmie to a new book that just came out. Tells her to read it and to let her know what she thinks.

Kittrell: And it was a book on the life of Ellen H. Richards.

Abdelhameid: Her full name was Ellen Henrietta Swallow Richards – and she was a chemist, MIT-trained. In fact, she was the first woman to attend MIT in 1871. She mostly focused on sanitation and water quality, and her work led to some of the first-ever state water quality standards in the nation. But there was something bigger driving Ellen’s research.

Horrocks: She wanted to apply scientific principles to everyday problems.

Abdelhameid: According to Ellen, science was the answer to all of the world's problems, including the problems of the home. And in her view, we could use science to cook better, more nutritious food. To clean our homes better. I should say, the “we” here is really women. That’s who was usually concerned about these sorts of things.

So Ellen insisted that women needed to have opportunities to learn about science, like chemistry, physics, botany, but only in the pursuit of becoming better homemakers and mothers. And soon, Ellen’s work would spawn a brand new field – it was called home economics.

Sutton Lewis: Home ec.! I loved home ec.

Abdelhameid: Most commonly probably known as home ec. I don't think anybody really says the full name. The economics part refers to using time and energy economically, but basically, it was the science of everything domestic. And as great as that all sounds, it’s important to note that the conference that launched this new shiny field took place annually at Lake Placid in a resort that banned Black and Jewish people. And the field of home economics itself would remain segregated for decades.

Sutton Lewis: Yikes. Oof.

Abdelhameid: Yeah, yeah.

Abdelhameid: The history of Ellen and of home economics was laid out in the book Flemmie’s teacher recommended, though the book mostly skips over the field’s racism. And if Flemmie knew anything about that, it didn’t deter her. She was inspired. Imagine – she probably would’ve been twenty years old at the time, reading about how this new burgeoning field could help people live better lives. And around the same time that Flemmie was being introduced to all of this, there was something else that happened.

Horrocks: She had a close family member, one of her sisters, died of something called pellagra.

Abdelhameid: Her name was Mabel Kittrell. She was Flemmie’s older sister and was twenty-two years old when she died of pellagra.

Horrocks: It's a vitamin deficiency.

Abdelhameid: Specifically a deficiency of niacin, or vitamin B3. And during the 20th century, pellagra was widespread in the South where low-wage Black laborers like Flemmie’s sister Mabel lived off of salt pork, corn meal, and molasses. It’s a diet that’s low in niacin, or at least the kind that our bodies can readily absorb.

Poor Black Southerners who developed the disease would get these rough, scaly skin sores all over. They would develop early signs of dementia – lethargy, confusion, tremors. And if left untreated for years on end, pellagra is deadly. Like in the case of Flemmie’s sister, Mabel.

Horrocks: And she never talks about this in her records, but I, you know, was able to find that out in public records. She becomes very keenly interested in nutrition and vitamins.

Abdelhameid: And here is this woman, Ellen Richards, talking all about the science of nutrition and how we can use science to make sure no one goes hungry. I can see why it would resonate with Flemmie.

Horrocks: And so this kind of personal connection, right, is not one that she draws, but the work of the historian is to say there probably is a connection here, right? A person who feels these kinds of losses very deeply and gets inspired to do something on a big scale.

Abdelhameid: Flemmie graduated with a Bachelors in Home Economics in 1928 and went on to do graduate work at Cornell, first for a master’s and then she went to do her Ph.D in Home Economics in 1936.

Sutton Lewis: Okay, Flemmie is graduating from Hampton and then doing graduate work at Cornell, getting a Ph.D. in home economics in 1936, an African American woman – that's pretty incredible.

Abdelhameid: She actually was the first black woman to get a Ph.D. from Cornell, and one of only four hundred women in the whole country to get a doctorate that year.

Sutton Lewis: A Black Ivy League graduate in 1936, who takes her brilliance and applies it to try to help the Black community? That, that's very impressive.

Abdelhameid: Yeah, and to kind of take that further for her thesis, she decided to look into nutrition in the Black community in Greensboro, a city one hundred miles east of Henderson, North Carolina where she grew up. This was the 1930’s, in the midst of the Great Depression. And Flemmie wanted to understand how all of this was impacting Black families, specifically in terms of what they fed their newborns and young children. So she went door-to-door, visiting the homes of Black families in the Greensboro area and asked them. She interviewed Black parents and had them fill out daily charts logging their meals and what they fed their newborns, and she surveyed doctors and midwives at the local hospital. What she found parsing through all of that data was damning. She found that Black infants died at a rate that was nearly twice that of white infants. That most families had, on average, three children, and of those three on average, two wouldn’t make it to adulthood.

But, Flemmie didn’t stop there.

Horrocks: She is able to show, through meticulous research, that through certain kinds of feeding…

Abdelhameid: Like using formula when milk was in short supply.

Horrocks: You could save babies' from starving to death. That must have been an amazing achievement, right? To feel that you could use science to keep people alive. And that you didn't need to be a certain kind of medical expert, but that by working with people and understanding them, you could be a real value to your community.

Abdelhameid: Flemmie got her start in nutrition, but it didn't take long for her to expand to other things. She wanted to know what it takes to raise a child. Start to finish. Body and mind. All of it. The science of it.

Horrocks: That is a really strange concept, I think, to a lot of people today. And it strikes at the heart of home economics, which is, you don't want to think that there's a science to people loving you, right? And like, making a house a home. And home economists would say there is, that there actually is an art and a science that can be identified and studied and pinned down. And again, I think part of where home economics just hits such a cultural soft spot is this idea that you have to be taught how to take care of a child. When so much of our cultural messaging is that some people are born knowing how to do it.

Sutton Lewis: Exactly! Certainly you know how to hug and love and cuddle and kiss a child, but who knows how to enrich a child? That's not something that you are born knowing. I mean that really hits home with me, the concept of there being a science that can be identified and studied and pinned down. I truly believe there are skill sets that parents can actually learn. And we all know to varying degrees just loving children just isn’t enough. Every parent should hear this.

Abdelhameid: Yeah, I think, looking through Flemmie's work and her life, she agreed with that and she had the same sort of understanding and approach. So after she graduated, she set up research labs. First at Bennett College in North Carolina, then at Hampton, her alma mater, and then in the 40s, at Howard University in Washington D.C. And these labs were really nurseries where she could closely observe children and develop the art and science of raising them.

And Flemmie was especially interested in knowing what these nurseries could do for poor kids. Kids whose families didn't have a lot of resources. Could a really good nursery prepare them for school? Could it close the academic gap with more privileged students? And in the long run, could it change their lives? In the 60's, Flemmy and a team of researchers decided to find out.

=== BREAK ====

Caffey-Flemming: Dr. Kittrell, let me tell you, she was my idol. I really and truly loved her.

Abdelhameid: That’s Dolores Caffey-Flemming, who you heard at the beginning of this episode. She got her bachelor’s and master’s in child development from Howard in 1968. And when Dolores thinks about Flemmie Kittrell, there’s one particular memory that comes to mind.

Caffey-Flemming: For 4th of July, I was supposed to go to Rock Creek Park with my boyfriend. We were having a cookout for the day and everything. But, I had to meet with Dr. Kittrell in the morning.

Abdelhameid: And that particular day, they were reviewing an assignment Flemmie had given Dolores.

Caffey-Flemming: I had completed my assignment, but it wasn't to her liking.

Abdelhameid: They go over the assignment, and then the phone in the Home Economics office rings. It’s for Dolores.

Caffey-Flemming: My boyfriend was wondering, you know, what time are you going to be finished? Because it was past the time we were supposed to be going. Next thing I know, she took the phone from me and she said, Young man, do you understand that she has work to do? She doesn't have time to talk to you today. And so, I was so embarrassed, I was like, oh my gosh, but she, she meant it.

Abdelhameid: Flemmie could be tough. But it sounds like Dolores was glad to take directions from her. She’d been doing it since they met. It was Flemmie who’d told her to study child development in the first place. And hired her to work at the nursery.

Every part of this nursery was meticulously planned. The children were fed nutritious, homemade meals – cooked and planned by students in the Home Economics Department, of course. The nursery was bright. It had books, puzzles, a terrarium, swings, and a slide. And the children got check ups from doctors and nurses at Howard’s Medical School.

Flemmie also had rules about how the nursery staff should treat the children – Eye contact. Give them hugs. And they had to smile at them, too. Here’s Flemmie again:

Kittrell: I think that, uh, in working with children, this is very evident, that if you smile at a child or have a pleasant face at a child, he will eventually come your way. So that looks like I could be a good kidnapper, doesn't it? [Laughs]

Abdelhameid: Now, a lot of the time the nursery was taking in the sons and daughters of Howard doctors, professors, and other staff affiliated with the university, kids with pretty successful parents and some level of access to resources, but Flemmie wanted to know what could a good nursery do for poor kids. How much of a difference could it really make? So in 1964, Flemmie and her team got to work to find out. They started with the kids right next to the Howard campus, in poor, mostly Black neighborhoods. Home economics students went door to door looking for candidates.

There was a long list of requirements. Kids had to be at least three years old, no older than three years, six months. They had to be in good health, have good vision, speak English, etc, etc. And they had to agree to be subjects in a research study. But the nursery was offering parents high-quality childcare at a world-class institution for free because the federal government was footing the bill. It was a pretty good deal even with all those requirements.

They got two hundred interested families. And from there, the team put thirty eight children in the “experimental group.” These were children who were admitted to the nursery – and they put sixty children were in the comparison group, a similar cohort that was not admitted to the nursery.

And so every weekday morning, a stream of little research subjects toddled off of a school bus, into the lab.

Caffey-Flemming: And that was a part of our training was to be able to observe and take notes.

Abdelhameid: And these notes were thorough. Here’s an example:

9:40, the Head teacher has entered the area and proceeds to play with Norma. Norma is playing with some dolls. The teacher encourages Norma – who was quote “one of the most backward children in the nursery.” Another child named Greta comes over…they tug at the doll. And Norma tries to hit Greta on the head with the doll…and then, another child [laugh] named Judith comes over…

Sutton Lewis: Okay, I have to go back to the toddler center experience I mentioned earlier. As a parent, you watch this and you're aghast, but the researchers look at this as a really interesting study of human behavior in small children. And in my experience they, they had all sorts of theories that made this interplay so much more significant and useful than just somebody bopping somebody over the head. And so, this stuff is golden. golden.

Abdelhameid: Yeah, and the research questions they were asking here couldn't be any bigger. Or more relevant at the time.

Reporter: The first thorough study of Negroes and how they live in this country was completed only a few months ago.

Abdelhameid: In 1965, the U.S. Department of Labor published a big, sweeping report written by a white sociologist named Daniel Moynihan. It was called The Negro Family: The Case For National Action, though it was better known as just the Moynihan Report.

Reporter: Daniel Moynihan, until this summer, Assistant Secretary of Labor, was in charge of the study and was staggered by it. Moynihan says the Negro family structure is collapsing.

Abdelhameid: The report was actually meant to be an internal document, but somehow it got leaked to the press, and well, it took off from there.

Moynihan basically said the Black community was in crisis. He blamed three centuries of slavery and continuing anti-Black racism, and he concluded that as a result, Black families were essentially broken.

Horrocks: There are famous lines from that report that talk about essentially webs and tangles of pathology. Of, you know, absent fathers and overbearing mothers. It is the basis for a very unfortunate number of stereotypes about black families in this country today.

Abdelhameid: Moynihan was a white man, coming in and detailing everything he thought was going wrong with Black communities. The report was then and continues to be extremely controversial. And Flemmie’s thinking was actually in some ways very similar to Moynihan’s. She’d also been studying Black families, had written about the challenges they faced.

She wrote that most Black children don’t have quote “constructive” early years. And like Moynihan, she attributed many of the problems Black families faced to the legacy of slavery and the damaging effects of poverty.

But instead of writing about “tangles of pathology,” Flemmie took the dire statistics and went in a different direction. A more hopeful one. She insisted that there were tools that could help, and advocated that they be given to Black families.

Horrocks: And this is where that divergence between people who work closely with families on finding solutions to problems versus the people who see the people as problems, right, who see the family members as problems to be solved.

Abdelhameid: Flemmie rarely, if ever, talked about racism explicitly, at least not in public. She just got on with the work of problem solving, figuring out what worked and what didn’t, but…

Horrocks: She's also making what you could see now as an anti-racist argument that there are not communities of bad parents or bad families. There are people who have not been given support, and that with government and intellectual and academic support, people can become amazing parents because they have that potential.

Abdelhameid: If the media was running with the Moynihan Report, saying Black families were broken, Flemmie was saying, disadvantaged Black families would thrive with support. And that part of that support was giving them a great nursery. So how much of a difference could that really make? They were about to find out.

In 1968, four years after the nursery study began at Howard, the federal Children’s Bureau released a ninety two-page report of the findings. And even though the research team had looked at a whole range of outcomes, a lot of the final report focused on one in particular: IQ.

So a lot of people think of IQ as an objective measure of intelligence. That view’s become increasingly controversial. But back in the 60s, the report writers were explicit that that’s not how they thought of it. It wasn’t about kids' intrinsic abilities. Cultural disadvantages could result in lower scores on these tests. But at the same time, those scores still mattered. Because they predicted other culturally unfair measures of success.

So the normal range for IQ is considered to be between 90 and 110. At the start of the experiment, the average for the kids in the experiment was in the low 80s.

Two years later, the average IQ of the children at the nursery had shot up by more than 14 points, putting them squarely in the normal range. While the comparison group – these were the kids who weren’t admitted to the nursery – their IQ only went up by only four points. The children also made gains on two other tests related to language ability, grammar, and comprehension.

And then, there were those less quantifiable changes. When researchers asked parents to reflect on what the nursery program had done for their kids, they said things like this:

Cindy was shy and selfish before coming to the nursery school. She talks now and is not selfish.

The nursery school has helped Teresa to think. Her conversations now make sense.

The kids in Flemmie’s care seemed to be doing well. But what about later? Would an early boost set them up for later success?

So the researchers followed the kids for a few more years—through kindergarten, and the first few grades of school. At first, these kids got some extra supports, like free breakfast and lunch, but in the third grade, the program was over. No more special supports. They were attending public school like other kids, and monitored to see how they were doing.

And in researchers’ final report, they are in a totally different place than when they started. By the end of the fourth grade, the IQs of kids in the experimental group had dropped way down, and were no higher than the comparison group.

And this report is gloomy. I don’t know if I’ve ever read a report quite as openly negative as this. It says that this is yet another program that showed “glowing early promise” that soon began to fade. But that it’s important to report on failures—like this program. Yeah, they called this program a failure. And so to the core question, can preschool ensure the later success of low-income children? The researchers regretfully concluded “No.”

So what was the point of all those meals and hugs and activities? As far as these researchers were concerned, just to find out what doesn’t work.

But the story doesn’t end there.

Lyndon Johnson: Today we’re able to announce that we will have open and we believe operating this summer coast to coast some two thousand child development centers, serving possibly a half a million children.

Abdelhameid: In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson made a big announcement.

Johnson: This means that nearly half the preschool children of poverty will get a head start on their future.

Abdelhameid: Head Start was a crucial part of President Johnson’s War On Poverty. Now, this was 1965. Flemmie’s nursery project hadn’t wrapped up yet. The gloomy report wouldn’t come out for another few years. And there was a lot of optimism about what an early intervention like this might do for a kid living in poverty.

Lauren Bauer: So the theory of change of the War on Poverty was to stop poverty before it starts.

Abdelhameid: Lauren Bauer is a fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution and has studied the Head Start program extensively.

Bauer: One of the ideas that was really generated during this time was the idea that poor children don't have to be poor. And because you were born poor, it doesn't mean that you have to be for the rest of your life.

Abdelhameid: The early incarnation of Head Start was a much more modest intervention than Flemmie’s. Instead of two years of preschool, Head Start was just an eight-week summer program.

But over the years, it’s expanded to serve kids ages three to five years old across the US. The federal government pays for about a million kids across the country to attend preschool for free each year. Some kids are in part-day programs, some in full-day. All of this costs about ten billion dollars a year. And it includes Early Head Start, which started in 1994 to serve kids from birth to age 3.

But in the early 2000s, the department of Health and Human Services started a massive study to see whether it was working. It was called the Head Start Impact Study. They ended up putting out a series of reports over the years. And just like that gloomy study of Flemmie’s kids, they found that the effects of Head Start didn’t seem to last. Kids would participate in the program, have a nice pre-school experience, some small improvements in cognitive skills, but pretty soon, the gains they made faded out. By the third grade, the researchers couldn’t detect any lasting effect of Head Start.

Bauer: Surely it makes sense that if you get a tremendous education when you're four and a terrible education when you're five and six and seven, how much do we expect your education at four to protect you against what's happening when you're eight?

And that's a lot of where the conflict comes in because you have people who frankly don't really love investing money this way being like, well, we expect a lot of it. You're telling us it's the greatest thing that's ever happened. Why aren't they doing better in third grade?

Abdelhameid: But Lauren Bauer and others decided to look deeper and found a few issues with the study. Some very basic things.

Bauer: Random assignment didn't work. It was not blind, much less double blind. And, there were plenty of kids in the control group who actually ended up going to Head Start because their parents really wanted them in Head Start, and sometimes they went to the center where the random assignment went sideways and sometimes they just went to the center across the street and said, oh, no, no, no, no, no, my kid is going to Head Start. I don't care if there was this experiment where they told me I couldn't.

Abdelhameid: So like a lot of sociology experiments, it was hard to create that experimental ideal: a randomized, controlled, double-blind study. But with some fancy math, you can parcel out the effects of Head Start. Take that, and other studies, and researchers have found that actually, the Head Start Impact Study missed something big. Head Start works. It might not be obvious in third grade test scores…but keep following those kids…and the benefits of Head Start become clear. Because study after study has found that kids who go to Head Start are significantly more likely to graduate from high school.

Bauer: And like we're talking like up to ten percentage points, which is a big number. And it's also true that they've been more likely to go to college. And even in some studies, graduate from college and that too, same trajectory, that's life changing for a child who grew up in poverty in the 60s and 70s. To be a child who grew up in poverty in the 60s and 70s and be more likely to have graduated from high school and go to college—like those families are living different lives.

Abdelhameid: And it’s not just the kids who go to Head Start that get a boost.

Bauer: There are second generation consequences. So the kids of mothers who went to Head Start are more likely to graduate from high school, less likely to be teen mothers, less likely to have a criminal record. Like, going to Head Start in the early days not only changed your lives, it changed the trajectory of your family.

Abdelhameid: Lauren says Head Start works best when kids are in school districts that keep offering additional support after the preschool program ends. In that case, you don’t see that fade out in the early years of school. But even just Head Start alone, it pays off.

So you have to ask if Head Start is so effective, why would the effects disappear in the third grade and then come back later on in life? Lauren thinks it’s a lot of non-cognitive skills

Bauer: A study that I did saw increases in self esteem and other sort of non-cognitive outcomes, so self control, self regulation, so we saw that. And so if those things are happening, maybe in third grade the kid could sit still through the test, but still didn't know the information they were tested on. But that kind of stuff sure helps you graduate from high school. Like, can I persist through this terrible high school? Yes, I can persist because I learned how to self regulate because I got to go to preschool.

Sutton Lewis: Well, I know for certain that I was actively interested in pouring things into my children when they were really young without a real sense that it was going to pay off by third grade. I mean, all the things that are part of a Head Start experience, playing, interacting with other people, their little peers. These things, learning how to relate to people, learning how to argue over a toy successfully, learning how to sit still as Lauren said. They really do serve you. Maybe you’re not grasping spelling or some of the fine points of academia in third grade, but you’re learning the way to learn. So it really does make sense to me that you can have a successful program that doesn’t bear fruit early. And if it doesn’t bear fruit in the third grade, it doesn’t mean that it was a waste of time or money.

Abdelhameid: So that brings us back to the question, does Head Start work? Lauren’s answer is an emphatic yes. And all of this is part of Flemmie’s legacy. Flemmie’s role in Head Start been a bit tricky to piece together, but we know her work wasn’t just a precursor to the program. She was part of it. By 1965, she was a recognized expert in child development and in running these kinds of programs. So when Head Start launched, she was deeply involved, creating instructional materials, training child care workers. She actually trained about two thousand Head Start workers.

Since 1965, Head Start has served more than thirty eight million children. It’s a massive, well-known federal program. But when people talk about the origins of Head Start, Flemmie’s name doesn’t usually get mentioned.

Horrocks: She's kind of cited as a footnote in Head Start because the big federal money does not really go to people in her field. It goes more to male child psychologists and folks like Sargent Shriver really get a lot of the credit for Head Start. He's always called the father of Head Start.

Abdelhameid: Sargent Shriver was a lawyer – Yale graduate – and the brother-in-law of President John F. Kennedy. And after Kennedy was assassinated, Shriver was tapped to head up President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty program.

His name pops up a lot in histories of the Head Start program. Flemmie’s name, on the other hand, is a bit harder to find. And sometimes her name doesn’t show up at all.

Sutton Lewis: And that ladies and gentlemen is why we have Lost Women of Science. Yet another instance where a woman scientist's work has been swept under the rug but no longer.

Abdelhameid: You’re absolutely right, Carol. And by the way, there’s one other reason why Flemmie in particular has been forgotten. Home economics, the field that Flemmie is so passionately rooted in – was falling out of favor.

Horrocks: By the 1960s people are already starting to disparage the field. To a lot of people outside looking in, it lacked focus. Right, like a general degree in home economics, without further inspection, just kind of looked like a degree in keeping a house.

Abdelhameid: This is also right about the time that early childhood development becomes its own field of research. It’s not falling under the banner of “home economics” anymore.

Horrocks: And in the post-World War II period, a lot more men enter that field as a function of the G.I. Bill. A lot more men are working with child development and all of those areas. And women start to really get pushed out.

Abdelhameid: And as all of this is happening, Flemmie was not really around to promote her research in the field or defend home economics. She wasn’t in the country that much. She was traveling to the Congo, Liberia, India, studying malnutrition, helping set up Home Economics departments abroad.

Horrocks: If you were a top home economist, by the 1960s, you were almost never on campus. That's a problem.

Abdelhameid: And today, home economics doesn’t really exist in the same way it did during Flemmie’s lifetime. Most people know it as the middle or high school class where they made brownies or learned to sew. But Flemmie’s approach does live on. Taking early childhood very seriously, looking at children’s well-being holistically, that’ll be very familiar to any modern parent.

And of course, there’s Head Start. Thanks to Flemmie and others like her, tens of millions of kids have been through this program. It’s not just a safe place for them to go while their parents are working, but a place where they get fed, where they might see a dentist or a doctor for the first time. Where they get a boost to their self-esteem and skills that might just last through school, and high school graduation, and into the ways they parent their own kids. But at its core, Head Start is just a place where kids are surrounded by friendly faces playing with them, reading them books, and just smiling at them, like Flemmie insisted they do.

This episode of Lost Women of Science was hosted by me, Danya AbdelHameid.

Sutton Lewis: And me, Carol Sutton Lewis. It was written and produced by Danya with senior producer Elah Feder. Lizzie Younan composed our music. Alex Sugiura sound designed and mastered this episode.

We want to thank Jeff Delviscio, chief multimedia editor at our publishing partner, Scientific American and our executive producers Amy Scharf and Katie Hafner.

Abdelhameid: I also want to thank the Schlesinger Library, part of the Harvard Radcliffe Institute. Flemmie Kittrell’s oral history interview was recorded as part of the library’s Black Women Oral History Project.

Sutton Lewis: Lost Women of Science is funded in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and Schmidt Futures. We're distributed by PRX. See you next week!

---------------

Episode Interviewees:

Dolores Caffey-Fleming

Former Howard University student

Program Director of Project STRIDE, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science Willowbrook, California

Allison Horrocks

Public Historian

Lincoln, Rhode Island

Lauren Bauer

Fellow, Economic Studies

Brookings Institution

Washington, D.C.

Further reading/listening/viewing:

Flemmie Kittrell audio interviews, Black Women Oral History Project Interviews, 1976–1981, the Harvard Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library Institute

Kittrell, Flemmie, The Negro Family as a Health Agency, The Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 18, No. 3, The Health Status and Health, 1949

Baure, Lauren, Does Head Start Work?, The Brookings Institution, 2019

Horrocks, Allison, Good Will Ambassador with a Cookbook: Flemmie Kittrell and the International Politics of Home Economics, University of Connecticut, 2016

First report on Howard Preschool Experiment: Prelude to School: An Evaluation of an Inner-City Preschool Program, Children's Bureau (DREW), Washington, D.C. Social and Rehabilitation Service, 1968

Talbot, Margaret, Did Home Economics Empower Women?, The New Yorker, 2021

Zigler, Edward, and Muenchow, Susan, Head Start: The Inside Story Of America's Most Successful Education Experiment, 1994.