This week doctors announced they had completed the first successful transplant of a partial face and an entire eye. In May at NYU Langone Health in New York City, the surgery was performed on a 46-year-old man who had suffered severe electrical burns to his face, left eye and left arm. He does not yet have vision in the transplanted eye and may never regain it there, but early evidence suggests the eye itself is healthy and may be capable of transmitting neurological signals to the brain.

The feat opens up the possibility of restoring the appearance—and maybe even sight—of people who have been disfigured or blinded by injuries. Researchers caution there are many technical hurdles before such a procedure can effectively treat vision loss, however.

“I think it’s an important proof of principle,” says Jeffrey Goldberg, a professor and chair of ophthalmology at the Byers Eye Institute at Stanford University, who was not involved in the surgery but has been part of a team working toward whole-eye transplants in humans. “I think it points to the opportunity and importance that we really stand on the verge of being able to [achieve] eye transplants and vision restoration for blind patients more broadly.” But he cautions that the main obstacle is achieving regeneration of the optic nerve, which carries visual signals from the retina to the brain; this step has not yet been successfully demonstrated in humans.

Face and cornea transplants have been performed before, yet to the NYU Langone team’s knowledge, this is the first time a whole eye has been transplanted successfully (with or without a face). The first partial face transplant was performed in 2005 in France. As of 2021, nearly 50 face transplants had been conducted worldwide. In 1969 Texas physician Conard Moore claimed to have attempted the first whole-eye transplant in a human, but it was not successful. Amid criticism, Moore later retracted his claim, saying he had only transplanted the eye’s outer portion—the sclera and cornea. Although a subsequent analysis suggested he may, in fact, have transplanted the whole eye, it did not develop a blood supply.

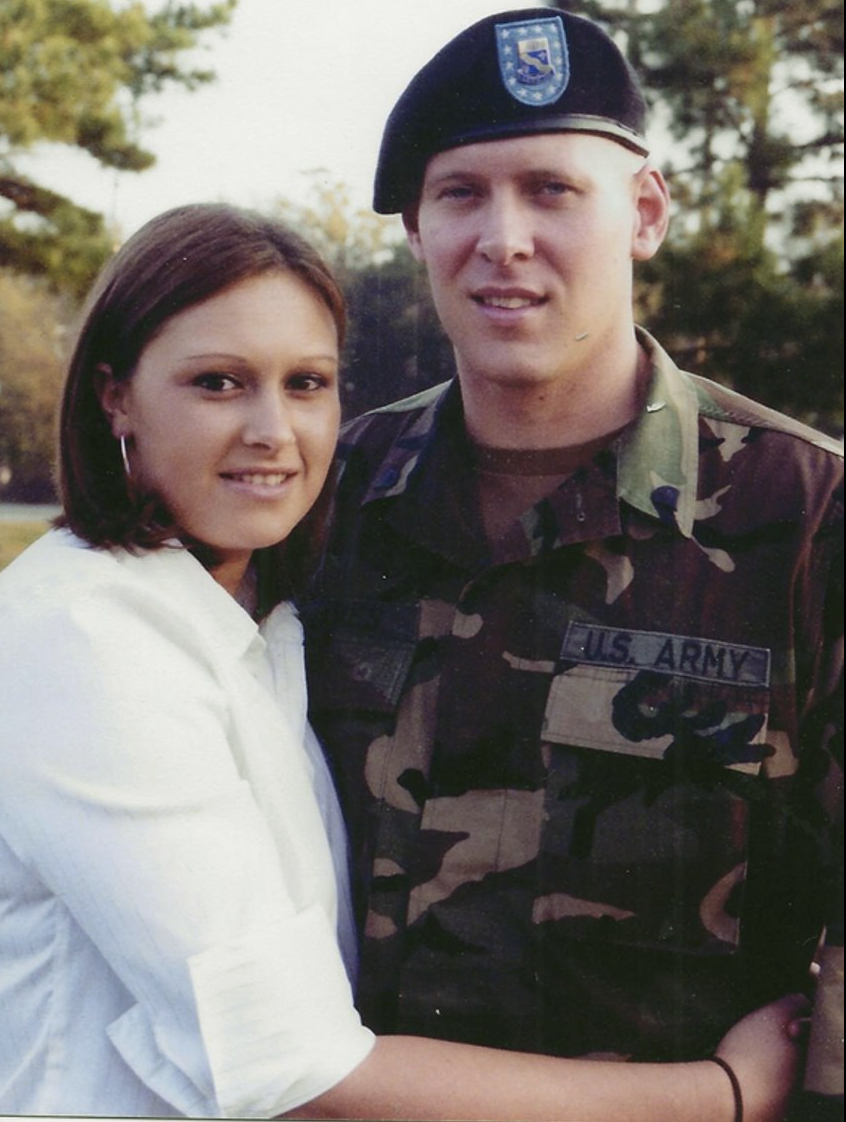

The recent transplant was performed by Eduardo Rodriguez, director of the face transplant program and chair of the department of plastic surgery at NYU Langone Health, and his colleagues. The recipient was Arkansas-based military veteran Aaron James, whose face touched a live wire while he was working as an electrical lineman in Oklahoma in June 2021. The accident left him with severe burns to the left side of his face, including his left eye, nose and lips, and extensive damage to his left arm, his dominant limb. James was transferred to a hospital in Texas, where he received multiple reconstructive surgeries. His left eye was removed because it was causing pain, and his left arm was amputated above the elbow and fitted with a prosthetic hook. He was in a medical coma for six weeks and he says he doesn’t remember anything from the accident and afterward until he woke up at the hospital.

.jpg?w=900)

Two months after the accident, Rodriguez and his colleagues at NYU Langone Health became aware of James’s case. Over the next year they discussed the possibility of a face transplant with Aaron James and his wife, Meagan. The decision was made to transplant the donor’s eye as well, because even if James never regained sight, the organ would help restore his face’s appearance. Like any transplant, there was a chance his immune system would reject the eye—but he would already need to take immunosuppressant medication for the face transplant.

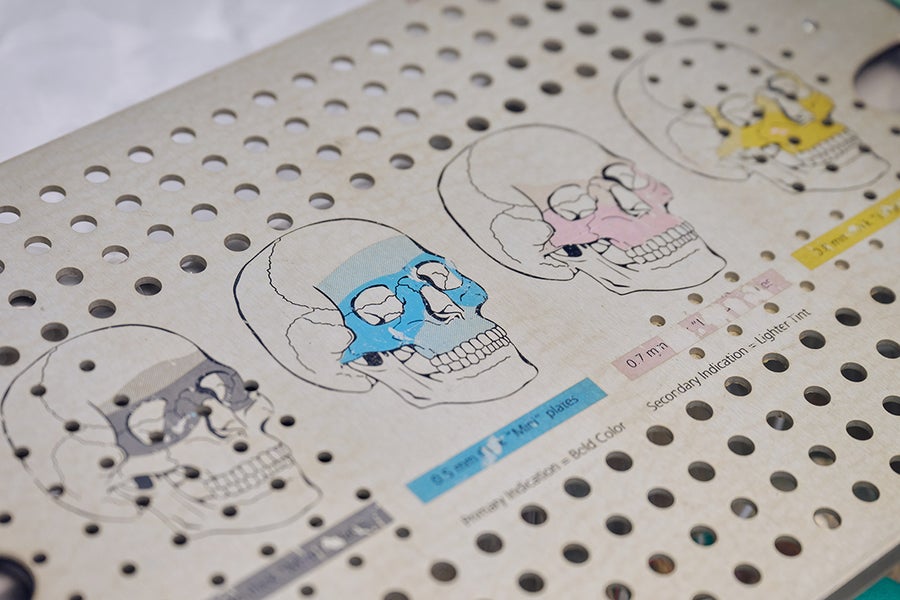

James was added to a transplant waiting list in February 2023, and on Memorial Day weekend in May a donor was identified: a deceased man in his 30s whose family consented to donate his organs. James and his family flew to New York City for the operation, which took place on May 27. The portions of the face that were transplanted included the nose, left eyelids and eyebrow, lips, underlying skull, nasal and chin bones, cheekbones, and all of the muscle and nerve tissue under the right eye. The entire left eye and optic nerve were transplanted, and stem cells from the donor’s bone marrow were transplanted along with them in the hopes of helping the optic nerve regenerate. The surgery itself lasted 21 hours and involved more than 140 people, including doctors, nurses and support staff.

James has since made a good recovery. He is able to talk, and although he does not have much ability to move his lips and facial muscles yet, Rodriguez says he will recover a lot of that ability with time. He can eat food on his own again now, and his wife Meagan says he has a big appetite. James was even able to attend his daughter’s high school graduation, and he says keeping his sense of humor has been critical to his recovery.

Rodriguez and the rest of the surgical team are very pleased with James’s recovery. “Everything that we’re seeing so far, no one expected,” he says. “Even if we don’t get sight, I will tell you at this point in time, everything seems incredibly exciting.”

As of six months post-transplantation, James does not yet report any vision in the transplanted eye. But measurements show the eye is receiving good blood flow and is maintaining normal ocular pressure, according to Vaidehi Dedania, an associate professor in the department of ophthalmology at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, who has been involved in monitoring the health of the donor eye.

“We ensured that the eye from the donor was in excellent health prior to the transplantation,” Dedania says. About nine days post-transplantation, “we were able to see that the blood is pumping through the eye and really getting a good flow and good oxygen to the entire retina through the retinal circulation. And that was really, really remarkable,” she adds.

Cross-sectional imaging of the donated eye’s macula (the central part of the retina) showed it was thinner after the transplant—but this had been expected because the blood supply had been necessarily disrupted, and a fair number of photoreceptors—light-sensitive cells in the retina—were still present, Dedania says. The photoreceptors appear to be responsive to light in preliminary tests. The medical team plans to conduct more rigorous follow-up testing soon to confirm this, however.

“The current studies seem to indicate that there’s the possibility of some communication between the [eye] and the brain,” says Rodriguez, who declined to comment further on preliminary findings that his team has submitted to a journal for publication. “However, we would like to validate that further, with a higher-fidelity piece of equipment by a nationally recognized expert.”

Scientists have been working toward whole-eye transplantation for many years. “This has been, I would say, science fiction for a long time,” says José-Alain Sahel, a professor and chair of the department of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, who has been working toward such transplants with Goldberg and others. Progress in surgical techniques and nerve regeneration have made this goal seem more attainable. Although eye transplants have been done in rodents with some success, the animals’ eyes are much smaller and less vascularized than those of humans. Goldberg and his team have done some research on pig eyes, which are more similar to humans’, but optic nerve regeneration remains a challenge.

“The fact that this surgery was successful is wonderful news,” Sahel says. He cautions that surgery is only a small part of the issues that need to be addressed in order to restore eye function, however. These include making sure the immune system doesn’t reject the donor eye, which is a challenge with any type of transplant. Then the corneal nerve—which carries sensory signals from the transparent part of the eye—must be reconnected. Yet the most complex part is regenerating the optic nerve. In order to do so, surgeons have to coax the nerve fibers to grow to the right place, which Sahel says could take months or even years. And complete optic nerve regeneration has not yet been successfully achieved in humans or other mammals.

Even if the optic nerve can regrow, there is the question of whether the brain will be able to interpret the signals from the transplanted eye. The brain has a lot of plasticity, so there is some reason to hope it may be able to adapt to the new input. Until these questions are addressed, “I’m doubtful that you will get a successful transplant in terms of restoring function,” Sahel says, adding, “I’m looking forward to seeing more results in this patient.”