As people attend indoor gatherings and prepare to travel this winter holiday season, cases of COVID in the U.S. have been tracking upward for the past month. This isn’t surprising—during the first three years of the pandemic, cases climbed in the weeks following Thanksgiving and through the beginning of the new year.

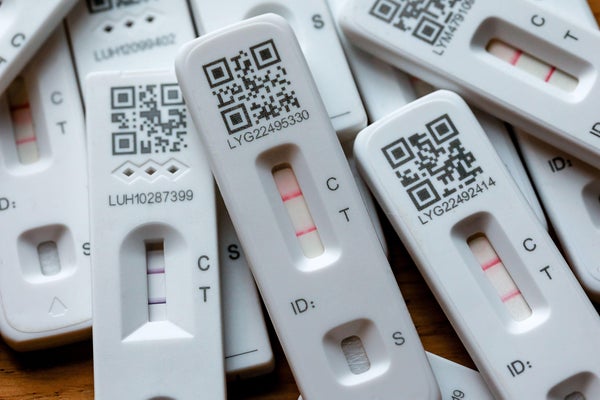

So these days a lot of people are taking COVID home antigen tests and looking for the pink line in the test window that indicates whether they are infected. But that line can vary in intensity from strong to faint. A number of scientists say those color changes may be able to give you more than a “virus” or “ no virus” answer by telling you if your illness is improving or getting worse—and thus revealing whether or not you should go to a family gathering or office party in your immediate future.

That’s not how these tests were designed, however. “I think it’s human nature to look at the intensity of the bands and say, ‘Gosh, it seems like I’m really positive, and maybe there’s more virus there,’” says infectious diseases physician and researcher Paul Drain at the University of Washington in Seattle. But, he says, it’s important to remember that these assays were not developed to be quantitative, meaning they can’t officially tell you how much virus is in the sample. They’re also not authorized by the Food and Drug Administration to do so.

Yet “it’s not a binary yes or no,” says physician and immunologist Michael Mina, chief science officer at eMed Digital Healthcare. Mina spearheaded large-scale COVID testing programs while at the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University at the start of the pandemic and for years worked on the development of next-generation immunological tools to aid in public health surveillance. “It’s a part of the basic chemistry of how these tests work to be semiquantitative.” The tests use antibodies, immune system proteins, that react to specific proteins—called antigens—that are part of the COVID-causing virus SARS-CoV-2. The line that you see on a test “is actually made up of millions and millions of little antibodies holding onto a dye,” Mina says, and the only reason those antibodies are able to stick to the line is that they’re also stuck to the virus antigens. “So the more virus, the more little dye molecules are going to line up on the line,” Mina says.

“In the work that we have done, and others have looked at this, the intensity of the line does tend to correlate with the amount of antigen in the sample,” says Morgan Greenleaf, an engineer at the Emory University School of Medicine. Greenleaf is also director of variant operations at the Atlanta Center for Microsystems Engineered Point-of-Care Technologies, one of the sites where companies send antigen tests to validate how they perform against new SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Although antigen tests are not, by any means, the only way to determine illness and help keep people from spreading COVID to others, Mina says, “they’re our way to see what’s otherwise invisible to us.” And he believes that that visual signal, and the idea that band intensity correlates with the level of virus, provides people with a tool for monitoring the course of their infection.

But, he says, that tool works only if someone has at least a couple of tests on hand. Consider what will happen if you only take one test, and it shows a faint line. “Then you’re kind of in this weird purgatory,” Mina says. The line could mean you’re at the very beginning of an infection, and the virus is starting to build up in your body. Or it could mean you’re at the tail end, and your immune system has nearly eradicated the microbe. So you could either be on the verge of getting sicker or nearly virus-free.

The key is being able to see the direction of a color change during a few days. If you test and see a dark band and then test again days later and see a lighter band, “you can breathe a sigh of relief and be like, ‘Okay, my body’s doing its thing. It’s clearing this virus. My immune system is working,’” Mina says. Conversely, if you’ve got symptoms, and you’re “seeing blazing positive for a week,” he says, you might want to reach out to your doctor. The antiviral Paxlovid could help and should be taken within five days of symptoms starting.

Mina also says that COVID antigen tests shouldn’t be used to completely alter your usual behavior—unless, of course, the test is positive. For instance, if you typically mask at large gatherings, you should continue to mask even if you get a negative result. And, he says, “if you’re positive, don’t go at all.” If you test positive, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says to stay home for at least five days and then, regardless of severity, wear a mask through day 10 of symptom onset or until you have two negative antigen tests 48 hours apart.

Drain says people should also be cautious to not overinterpret test results. For instance, “somebody can really have serious breathing issues and still have a very faint, positive line,” Drain says. In some such cases, although there’s little virus left in a person’s body, they are dealing with a potentially dangerous aftermath of fluid buildup in their lungs. “We don’t want to give people the impression that if your symptoms are severe but your line is very faint that it’s a mild infection, and you’re safe.”

Human error—for example, superficial swabbing that picks up little virus when a more careful swab would collect much more—is another important caveat to how much you can learn by looking at the band intensity, says physician Apurv Soni, who studies home testing. (Soni likens home antigen testing to making a cup of espresso: How a person does it affects the results. The amount of beans loaded, time the machine runs or amount of force applied when tamping down the grounds could all vary from one person to the next.)

Mina is a bit less worried about user error with swabbing except in cases where someone is right at the border of being able to see a line or not. “Maybe it can push somebody into negative territory if they’ve done a really poor job swabbing,” he says. But the tests show a positive band when there are only a relatively skimpy hundreds of thousands of viral particles per milliliter of sample. If you have a billion viral particles per milliliter—which is not unusual in the middle of an infection—you can miss 99 percent of them with a swab, and there would still be 10 million viral particles on the swab end, he says, which would show up as a very dark line.

Still, if you do compare lines on different days, avoid switching test brands if possible, Greenleaf says. That’s because there can be some variability in the limit of detection (LOD)—the smallest amount of virus that can be detected—between tests, as well as in how the LOD is measured, and that could affect color intensity.

Although buying several of these tests over the counter can be costly, depending on your insurance, the U.S. government offered to mail some free tests to the public late this fall. Some public health centers, including those funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration, make free or low-cost COVID tests available to people who are uninsured or members of underserved communities. Another opportunity for underserved groups is the National Institutes of Health’s Home Test to Treat telehealth program, which provides free COVID and influenza home tests for people who are not positive for these illnesses when they enroll. (For people who are already ill, the program offers treatment options.)

The positive lines on home tests often prompt anxiety and fear. But when used the correct way, the lines can also make planning get-togethers safer and simpler.