Donna Richardson’s pregnancy should have ticked all the boxes for a smooth delivery. At the time, she was a physically active, 30-year-old traffic officer with no underlying health conditions. Her water broke at 40 weeks, the sweet spot for labor and delivery, and her home in Washington State was a quick 15-minute drive away from the hospital. But as Richardson’s contractions intensified, her discomfort quickly escalated into piercing chest pains. “I was screaming at my husband, the nurse, really anyone who would listen, just begging someone to help me,” she says.

Richardson was rushed into an emergency cesarean section, which has a complication rate nearly five times that of a vaginal birth. After a tense 25-minute surgery and several hours of recovery, Richardson was reunited with her husband and newborn son. “He was a squirrely, wrinkly thing,” Richardson says. “But looking at him, knowing that we both made it through the night, I felt like one of the lucky ones.”

Her experience, which occurred in 2016, mirrors that of thousands of pregnant people who develop life-threatening health complications during and after pregnancy—resulting in worsening maternal death rates across the country. The U.S. is considered an outlier among wealthy nations in maternal health care. In 2020 the average maternal mortality rate of all high-income countries was 12 deaths per 100,000 live births, but in the U.S. that number was nearly 24. New research indicates the U.S. rate continues to climb annually, pushing experts to investigate the causes and search for solutions.

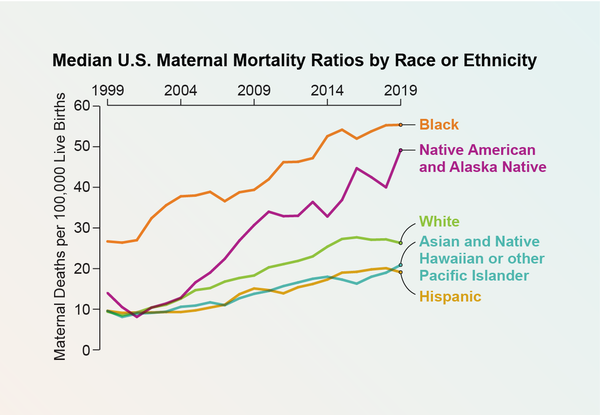

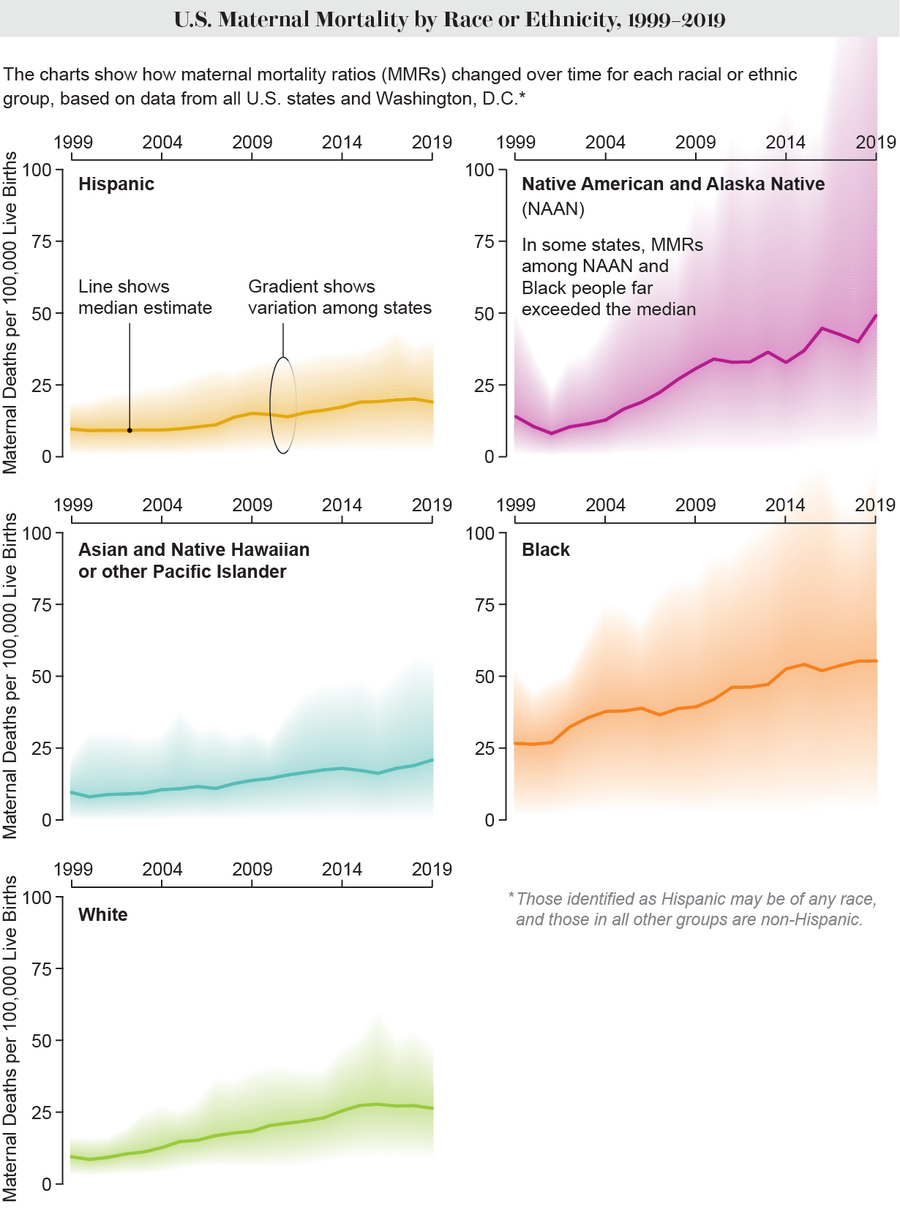

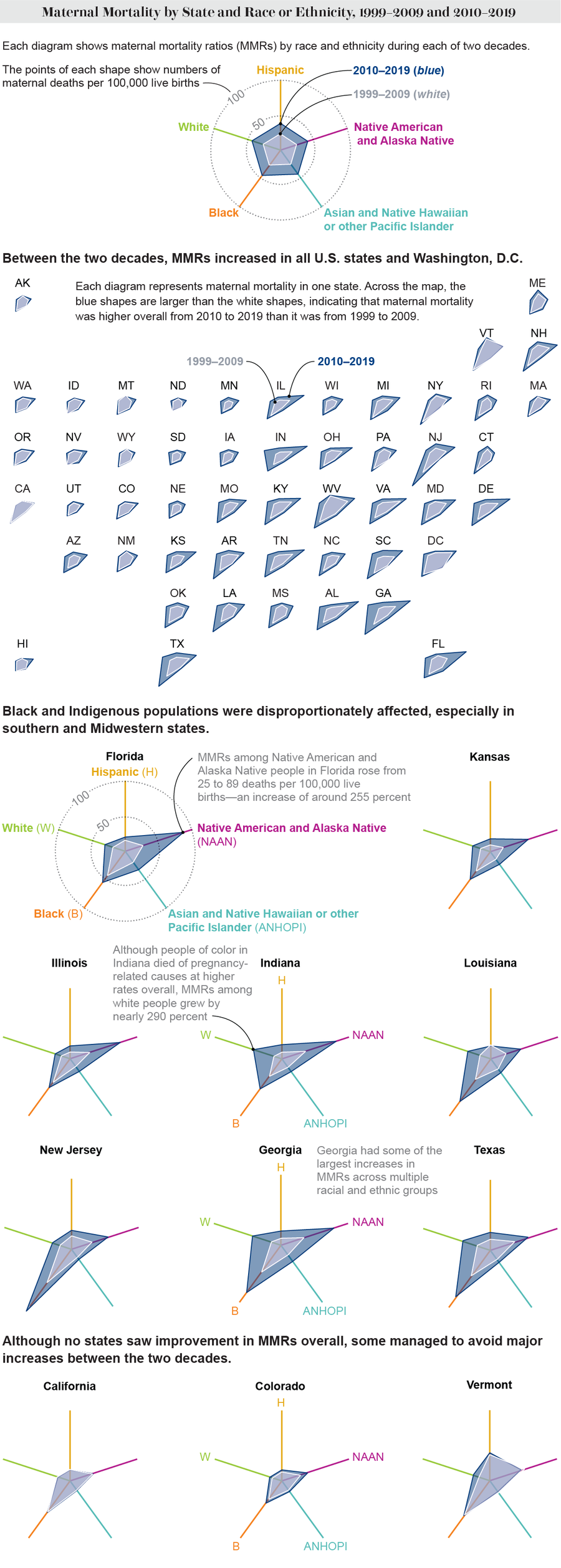

A new study published this month in JAMA revealed stark details about how U.S. rates continue to defy the global trend toward improvement. From 1999 to 2019, maternal mortality—defined in the study as a death during pregnancy or up to a year afterward—more than doubled in the U.S. Although deaths increased in people of all races and ethnicities, disparities persisted. Black people consistently experienced higher rates of maternal mortality, and Native American and Alaska Native communities witnessed an alarming surge: state median rates more than tripled.

Annual reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have long indicated a downward trend in health outcomes for pregnant people in the U.S. This was particularly apparent during the COVID pandemic, when people delayed seeking care, and maternal mortality rates rose by 40 percent from 2020 to 2021. But detailed, long-term data for racial and ethnic groups across all U.S. states were lacking, explains Allison Bryant, senior medical director for health equity at Mass General Brigham and a co-lead author of the new study. She says her team’s research fills those gaps.

“Our findings confirm that maternal mortality rates are both unconscionably high and rising and that there are dramatic inequities,” she says. “With this new data, we can examine those disparities state-by-state, group-by-group.”

The Causes of Worsening Maternal Mortality

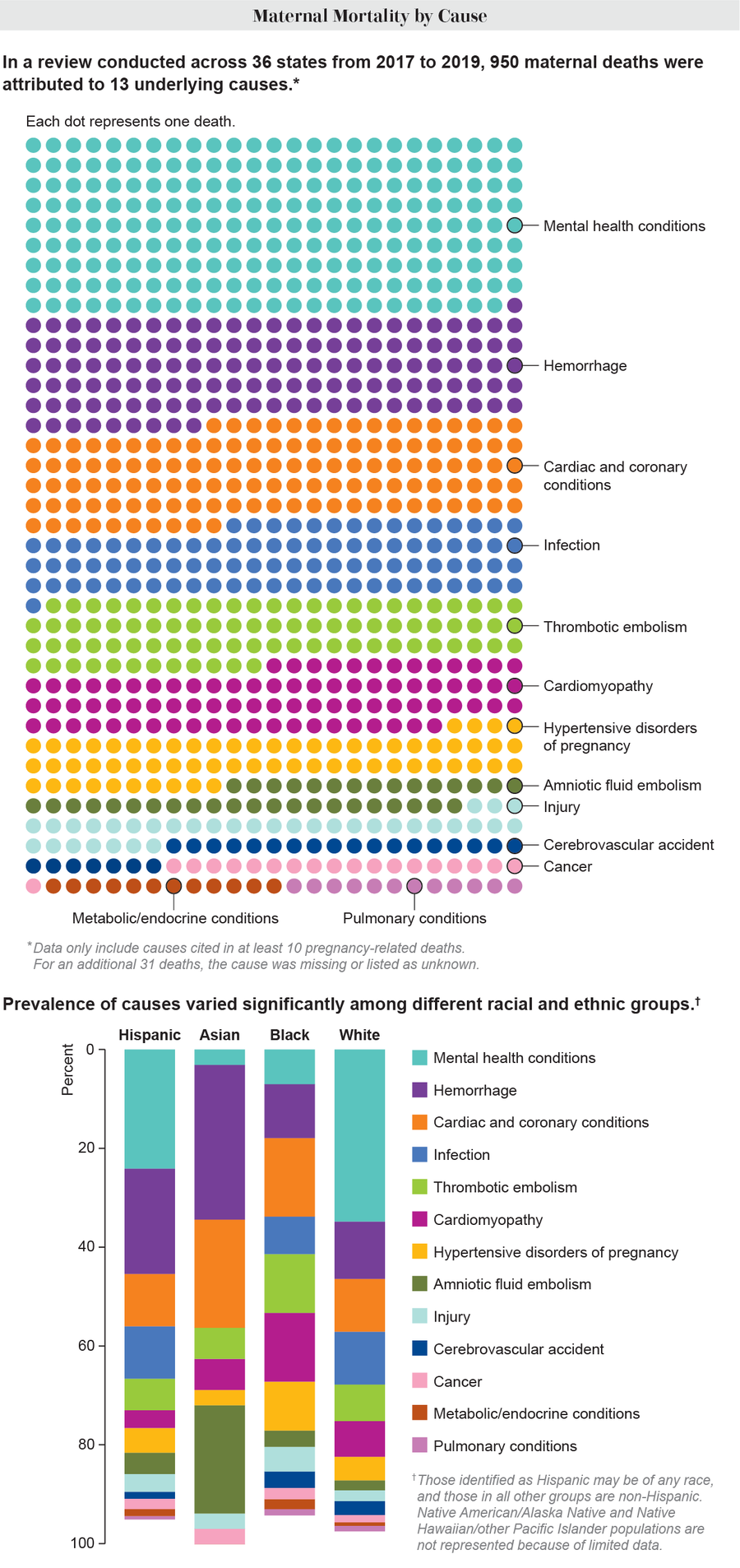

The annual count of maternal deaths amounts to several hundred across all states—a figure comparatively lower than fatalities from other medical conditions. But more than 80 percent of these cases are preventable, leaving researchers scrambling to understand why the rates are rising.

Research has shown that the proportion of people who are having children later in life or entering pregnancy with chronic conditions, such as obesity or cardiovascular disease, has grown over the past few decades. Both factors raise the likelihood of experiencing complications during pregnancy and childbirth. The increasing number of cesarean sections—a major surgery that isn’t always necessary—has also been linked to a greater risk of maternal death.

But focusing too narrowly on demographics, labor and delivery paints an incomplete picture of maternal health, says Lindsay Admon, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of Michigan Medical School. In fact, over the past decade, maternal mortality during labor and delivery has decreased in U.S. hospitals across people of all ages, races and ethnicities, which researchers say is a result of improved birthing protocols. This reduction in deaths during childbirth itself implies that other factors are driving the overall rising rates of maternal mortality.

“The riskiest time [for mothers] often comes after the baby is born. Yet most of the clinical and policy interventions we’ve seen in the past decade focus on improving care at the time of delivery and neglect the time before or after,” Admon says. She explains that new mothers face substantial risks during the year after delivery, ranging from physical complications, such as a deterioration in heart muscle, to mental health conditions, including postpartum depression.

A CDC report released last September said more than 30 percent of pregnancy-related maternal deaths occur between six weeks and one year after childbirth. The most common underlying cause of all pregnancy-related deaths for which a cause was identified were mental health conditions, which contributed to 22.7 percent of deaths. This surpassed hemorrhage, cardiac conditions and infection.

These findings shocked some health care providers and epidemiologists, who have traditionally defined the term maternal mortality as deaths that occur during pregnancy or within six weeks after delivery. The danger of this “fourth trimester”—the period between birth and 12 weeks postpartum—can be “an entirely different monster” for new parents, Richardson says.

During the second month postpartum, Richardson began experiencing panic attacks in response to seemingly innocuous triggers, such as the scent of latex or the sight of Instagram posts showing a friend’s giggling newborn. Night after night, terrifying dreams of the delivery room stole the precious sleep she managed to get between shifts of soothing her newborn son. She soon realized her emotional distress was connected to her pregnancy.

“Deep, deep down, a little piece of me blamed my son. And then I’d feel so guilty for even letting myself have that thought,” Richardson says. “I felt like a bad mother.”

It took seven more months for Richardson to receive a diagnosis and treatment for postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a type of trauma that develops after the difficult events of childbirth and should be diagnosed within the first few months after delivery, experts say. Postpartum PTSD is believed to afflict approximately 3.1 percent of people who give birth, but researchers believe cases may be vastly underreported because postpartum mental health conditions are not well studied.

Disparities in Care

Despite fervently reporting her symptoms to her doctor, Richardson says she was dismissed. “They told me, ‘You feel this way because you’re sleep-deprived from waking up to take care of your son.’ And I wanted to yell, ‘No, I’m sleep-deprived because I feel this way!’”

Shanti Moore, a registered nurse and birth justice coordinator at SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective in Georgia, says that people of color, such as Richardson, who is Black, are especially vulnerable to having their medical complaints overlooked.

“These disparities partly stem from being Black and having your concerns repeatedly ignored. I’ve experienced that dismissiveness at my own doctor’s appointments,” says Moore, who encourages health care providers to use active listening during their patients’ regular appointments. She is training to become a midwife in Georgia—a state that had one of the largest increases in maternal mortality in the new JAMA study. Bryant and her team affirmed that maternal health declined for all racial and ethnic groups across the country, but certain groups and geographical pockets were disproportionately impacted.

In addition to the recognized epicenter of the South, where a large population of Black residents are particularly at risk of poor maternal health outcomes, the researchers found elevated maternal mortality rates concentrated in the Midwest and northern Mountain states. These clusters were driven by high rates among Native Americans.

“People often criticize the South, while states like California and Massachusetts are commended,” Bryant says. “But as a health care provider in Boston, where we have a well-resourced health care system, I still see it’s not equitable for everyone. We have to look at all disparities, including in states that have great maternal health care at face value.”

Although 49 states have formal maternal mortality review committees (MMRC) to investigate pregnancy-associated deaths, only nine states, Washington, D.C., and New York City consider racial disparities and equity in their assessments. Admon notes that MMRCs provide local government officials with insights into their state’s specific maternal health challenges and identify opportunities for prevention—which is why it’s crucial for them to have an inclusive picture of the problem. On top of that, reviews are not consistently delivered by all committees. For instance, MMRCs in only 36 states reported their findings to the CDC between 2017 and 2019.

“The data coming out of these committees is the most valuable information we have to understand the maternal mortality crisis,” Admon says. “The more committees reporting their findings, the more prepared we are to prevent maternal deaths.”

One problem is that MMRC reports have become increasingly politicized, leading to inconsistencies in their creation and release. For example, Idaho recently became the first state to dissolve its MMRC after conservative lobbying groups decried the committee as an “unnecessary waste of tax dollars.” Experts attribute this politicization in part to the recommendations MMRCs make, which frequently involve addressing social determinants of health such as income, education access and racial discrimination.

“You can’t have a conversation about improving maternal health without looking at the structural factors that make some people more vulnerable,” Bryant says. “Do they have the transportation they need to get to the hospital? Do they have access to mental health resources? Is their educational level affecting the care they receive? These are the questions we need to ask.”

The Future of Maternal Health

Thirty-five states and Washington, D.C., have extended Medicaid postpartum coverage to ensure pregnant people remain insured for a full year after birth rather than the currently standard 60 days. These expansions have been shown to significantly reduce maternal mortality, particularly among Black people.

In states with poor maternal health outcomes, local clinics and reproductive health advocates have also worked to expand access to community-based doulas—nonmedical birth support workers who provide long-term physical, emotional and educational support to pregnant people. Last November the nonprofit Healthy Mothers, Healthy Babies Coalition of Georgia partnered with two Medicaid-managed care plans to launch a birth doula reimbursement pilot program. The program, which provided doula services to 175 pregnant Medicaid recipients, drew upon existing research demonstrating that doula services halve the likelihood of birth complications while lowering overall costs for state Medicaid programs. Similar programs that have been implemented in 11 states and Washington, D.C., have yielded promising results in reducing racial and socioeconomic disparities in maternal mortality.

Although these efforts are gaining some momentum, the future of maternal health in the U.S. is still murky. It’s unclear how last year’s Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade—along with the subsequent reintroduction of abortion bans across the country—will impact maternal mortality rates. Many health care providers are pessimistic. One national survey found that 64 percent of ob-gyns believe the Supreme Court’s ruling has worsened pregnancy-related mortality.

Other advocates and medical experts say the ruling only reinforces what they already know: the state of maternal health in the U.S. is dire and demands immediate action.

“It’s frightening, but I keep pressing forward because I’m hopeful that things will change,” Moore says, “because the other choice is to surrender, and I can’t do that.”

Despite her tumultuous labor and postpartum experience, Richardson continues to persevere, too. Her family is gearing up to celebrate her son’s seventh birthday next week. She explains the party plans as she drives to pick up his gift—a 27-piece doctor’s kit playset. “He’ll love it!” she says giddily.

“I’m so grateful I survived that day and kept pushing forward in the months after because it means I get to do this,” Richardson says. “I get to be his mom.”