A mosquito bite is usually just an itchy annoyance—but sometimes it can lead to serious illness.

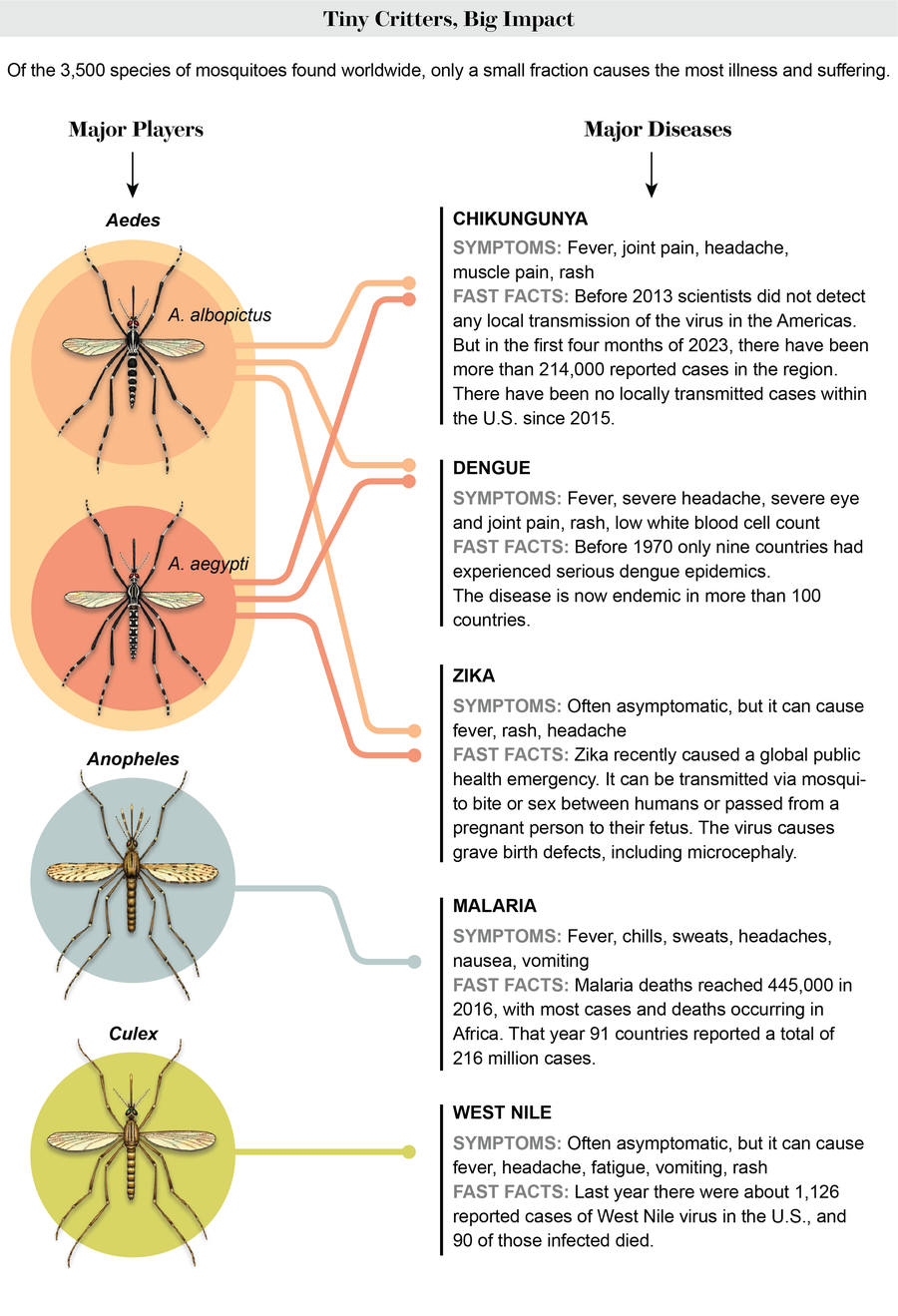

That’s because mosquitoes can carry a range of microbes that infect humans, including four species of malaria parasites. Members of the genus Plasmodium, these malaria-causing microbes hitchhike on female mosquitoes of the genus Anopheles and get transferred to humans when those insects bite us. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, malaria killed 627,000 people worldwide in 2020. The U.S. effectively eradicated the disease by 1951, although small outbreaks, usually carried here by infected international travelers, still pop up occasionally. As of press time, this spring and summer, seven people in Florida and one in Texas were reported to have caught malaria.

In addition to malaria, mosquitoes carry West Nile virus, which is the most common cause of mosquito-borne illness in the U.S. and is primarily transmitted by mosquitoes in the genus Culex. In 2022 1,126 Americans were diagnosed with the disease, and 90 people died from it. All told, the CDC tracks nine mosquito-borne diseases in a surveillance system dedicated to monitoring so-called arboviruses—viruses transmitted by arthropods—that are spread by mosquitoes and ticks. (Malaria, a parasitic infection, isn’t included in the database.)

“There are lots and lots of mosquitoes and lots and lots of mosquito-borne diseases that humans are impacted by,” says Sadie Ryan, a medical geographer at the University of Florida. Most of these infections are much more common in tropical climates and in less common in developed countries. Researchers are concerned that this might change as the geographical range of mosquitoes shifts with climate change.

As peak mosquito season looms over much of the U.S., here’s what to know about the blood-hungry vectors and the diseases they can carry.

How common are mosquito-borne diseases in the U.S.?

Overall, levels of mosquito-borne disease in the country are quite low and have been since the mid-20th century, when malaria was effectively eradicated through a nationwide campaign to spray insecticides and otherwise kill mosquitoes.

“Mosquito-borne disease in the U.S. currently, compared to historical [levels], is leaps and bounds lower,” says Katie Westby, a disease vector ecologist at Washington University in St. Louis. She notes that she’s more concerned about rates of tick-borne diseases such as Lyme disease and babesiosis. But Westby and other experts warn against complacency with mosquitoes. “By no means do I think that the situation is going to last forever without continued vigilance,” she says.

How big of a risk is West Nile virus?

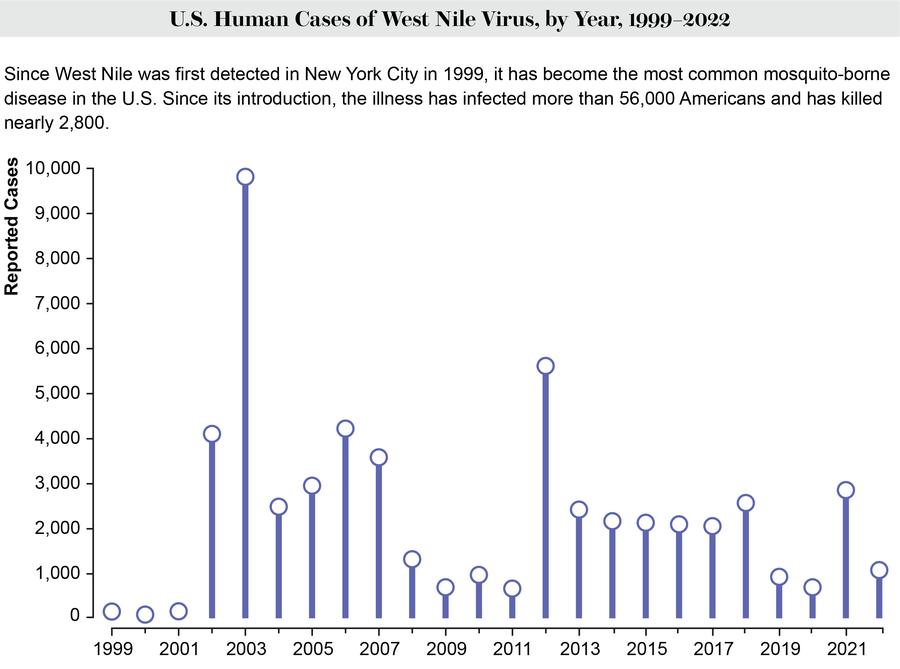

West Nile, which was first reported in the U.S. in New York State in 1999, is now the country’s most common mosquito-borne disease. Since its introduction in the country, the disease has infected more than 56,000 Americans, and it has killed nearly 2,800.

Unlike some pathogens, mosquitoes don’t catch West Nile by biting an infected person and then transmitting the disease to others they bite. Instead a mosquito picks up the virus by feeding on an infected bird and then transmits it to a human through a bite. While the virus’s avian origin reduces the odds of human infection, it also complicates management because neither vaccinating nor culling huge numbers of birds is likely to be a cost-effective and publicly palatable solution.

West Nile disease is “different for me than things like dengue and malaria because it is a spillover disease,” Ryan says. For both dengue and malaria, mosquitoes get infected when they have a blood meal from an infected person. With West Nile, “humans are the ‘dead-end’ hosts; we’re not the reservoir,” she says. “And so the management for West Nile has to be very different.”

What other infections do mosquitoes transmit in the U.S.?

Dengue also occurs in the nation at noticeable levels. As of June 1, the CDC had reports of 129 cases of dengue in U.S. states and 256 cases in U.S. territories this year. Last year the disease infected 1,188 people in states and 828 people in territories. Other recent years have seen fewer than 500 infections within U.S. states. A surge in dengue infections in Central and South America, however, has researchers concerned that this year’s infection rates may be unusually high.

Dengue is spread by different mosquitoes than those that carry West Nile or malaria; only Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus transmit dengue. These Aedes mosquitoes are particularly nasty because they can also transmit Zika and chikungunya, among other viruses. Fortunately, the CDC has no reported cases of either of these infections being acquired locally within U.S. states for several years.

Other mosquito-borne diseases also remain rare nationally. La Crosse encephalitis virus, which is principally carried by Aedes triseriatus mosquitoes, has caused, on average, fewer than 100 cases of human disease in the U.S. each year since 2003. And Jamestown Canyon virus has caused fewer than 300 known cases of human disease in the U.S. since 2011. Similarly, since 2003 the CDC has reports of fewer than 300 cases of St. Louis encephalitis, which, like West Nile, is principally spread by Culex mosquitoes that bit infected birds.

Louisiana has reported one case of eastern equine encephalitis this year. The CDC has never received reports of more than 40 infections of this virus in a year, and fewer than 200 people have caught it since 2003. This pathogen has a complicated life cycle: it is mainly transmitted among birds by a particular mosquito, although multiple other species of mosquitoes can pass it to horses and humans as dead-end hosts.

What are the symptoms of these diseases, and how are they treated?

Mosquito-borne diseases are challenging to diagnose. Many people don’t display symptoms at all: for instance, only about one in five people infected with West Nile and one in four people infected with dengue show signs of infection.

The high rate of asymptomatic infections can make spotting and controlling outbreaks more difficult. “You can never really be sure how much transmission is going on because a lot of the transmission that’s happening is kind of under the radar,” says Angelle Desiree LaBeaud of Stanford Medicine Children’s Health, who specializes in pediatric infectious disease and global health. “You have this population of people that isn’t necessarily showing signs or taking precautions to keep themselves from spreading infection.” (Because most of these diseases can’t be transmitted directly between people, those precautions focus on preventing additional mosquito bites that spread the virus to new carriers.)

And people who do notice an infection tend to appear in doctors’ offices with generic complaints such as fevers, headaches and nausea.

“They can present in a lot of similar ways to each other,” says Shelby Lyons, an epidemiologist at the CDC. “These diseases can be difficult to identify: their clinical signs and symptoms can mimic a lot of other diseases, and arboviruses aren’t always at the top of mind for clinicians.”

There are also no specialized vaccines or treatments for mosquito-borne viruses—doctors can only treat the symptoms.

What might this summer and fall look like?

The CDC doesn’t have a way of forecasting each year’s mosquito-borne disease season, Lyons says. “It’s really, really difficult for us to predict from season to season,” she adds.

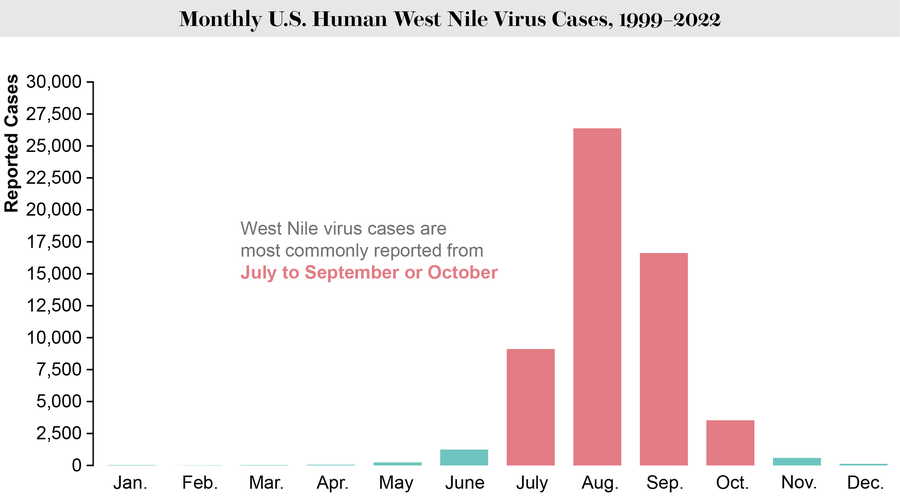

Mosquito-borne diseases are most common in the U.S. from July to September or October, Lyons says. During this season, her office monitors daily case reports for any concerning trends. So far infections have been reported from the Midwest and West, as well as the Southeast; most of those are cases of West Nile, of which there were 69 cases nationwide as of July 25.

Lyons says that infection rate is in line with previous years. “Overall, nationally, looking at the data, it really seems to not be very different from what we’ve traditionally seen,” she says. “It looks about on par with what we would expect.”

What factors affect the prevalence of mosquito-borne diseases in the U.S.?

First, the infection must be in the area—either in animal hosts such as birds (in the case of West Nile) or in humans who had previously traveled to one of the places where these diseases are more common and were bitten by a carrier mosquito there.

Typically, mosquitoes prefer hotter, wetter climates. “They like warm and humid conditions; they like to be in areas with lots of places to breed for their larvae to develop. Access to hosts is really important, [as are] shady sites for resting when it’s hot, access to sugar meals,” Westby says.

More northern parts of the country have traditionally had fewer mosquitoes—and fewer mosquito species—but that’s changing because of the climate crisis. As mosquitoes move into new territories, they will begin biting people who are less accustomed to thinking about the threat of mosquito-borne diseases, LaBeaud says. “Areas that, before, weren’t really ripe for these infections are now going to become ripe,” she says.

How can you protect yourself from these diseases?

Many Americans are protected by their lifestyle, unlike people in less developed countries. American homes are more likely to make use of window screens or even air-conditioning, which keep mosquitoes outside. And while construction, agriculture and other industries can put workers directly in insects’ paths, office jobs tend to further reduce exposure. “Who is exposed to mosquito-borne disease is highly related to socioeconomic conditions,” says Kim Medley, an ecologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

If you live in a home with outdoor space, reduce places where water can accumulate, such as garbage bins, potted plant saucers, birdbaths and other home equipment. A. aegypti and A. albopictus are known as “container species” because they lay eggs in small pools of standing water. The CDC recommends emptying and scrubbing out any such items once a week to reduce the overall number of mosquitoes.

The best step you can take to protect yourself from mosquito bites is to use an insect repellant recommended by the Environmental Protection Agency, such as DEET. And pay attention to recommendations and warnings from your local health department because that office will have the best knowledge of whether any mosquito-borne diseases have been reported in your area. If you’re traveling outside of the U.S., consult the CDC’s guidelines for your destination.

Don’t panic with every mosquito bite. Vigilance is key to ensuring that mosquito-borne diseases remain in check, but humans may never fully vanquish these pathogens. “Mosquitoes have been doing mosquito things for millennia, and they’re really, really good at it, despite our best efforts to keep them at bay,” Medley says.