Pancreatic cancer is one of the deadliest forms of cancer, with very few effective treatments. But messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines—famous for their ability to prevent COVID—are starting to show some promise against the lethal cancer. In a recent early-stage trial, half of pancreatic cancer patients who received a personalized mRNA cancer vaccine after surgery did not have a recurrence of the tumor a year and a half later. The trial, which was described in a study published on Wednesday in Nature, was small—with just 16 patients—and it will need to be replicated in larger studies.

“I am very supportive of the findings,” says Drew Weissman, director of vaccine research and director of the Institute for RNA Innovation at the University of Pennsylvania, who is a pioneer of mRNA vaccines but was not involved in the new paper. He adds that “it is not a definitive proof-for-use study. Larger studies are needed to determine effectiveness.”

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, the most common type of pancreatic cancer, has a mortality rate of 88 percent. It is the third leading cause of death from cancer in the U.S. and is becoming more common. Surgery is the main form of treatment, but the cancer has a 90 percent recurrence rate at seven to nine months. Chemotherapy is only partially effective at delaying recurrence. Other treatments, such as immunotherapy, are mostly ineffective.

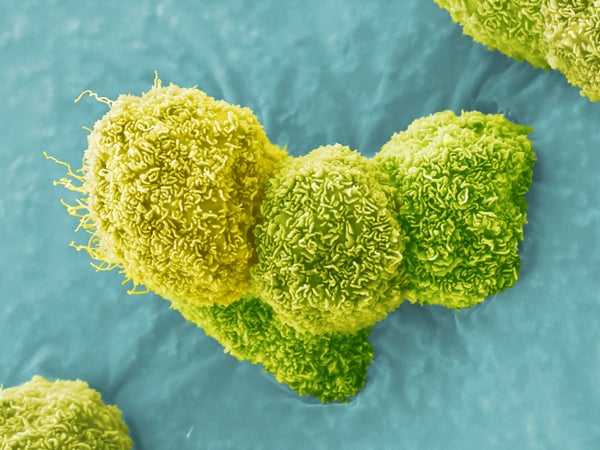

Pancreatic cancer often goes undetected until its later stages, when it is harder to treat. One reason it is so sneaky is that it generates relatively few of a type of surface proteins, called neoantigens, that mark it as foreign and trigger an immune response. Scientists had noticed that people who survived pancreatic cancer had a stronger response to these neoantigens from T cells, a type of immune cell.

In the new study, Vinod Balachandran, an assistant attending surgeon at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, and his colleagues targeted pancreatic cancer patients’ own tumor neoantigens using mRNA technology—the same technology used to create the remarkably successful COVID vaccines. The experimental vaccines used by Balachandran and his colleagues were produced by BioNTech, a company that developed one of the COVID vaccines with Pfizer. The researchers vaccinated a total of 16 patients. After surgically removing the tumors, they treated the patients with mRNA vaccines tailored to each person’s specific cancer, as well as an adjuvant, a substance that increases the effects of vaccines. Fifteen of the participants were also treated with chemotherapy.

Eight of the 16 patients generated a strong T cell response to the vaccines. At a median follow-up time of 18 months after the treatment, these individuals had longer survival, without a recurrence of their cancer.

The study was small and involved only white patients. And the therapy—which is expensive—does not work for everyone with pancreatic cancer. Nevertheless, experts say it is a promising development for a disease with such limited treatment options.