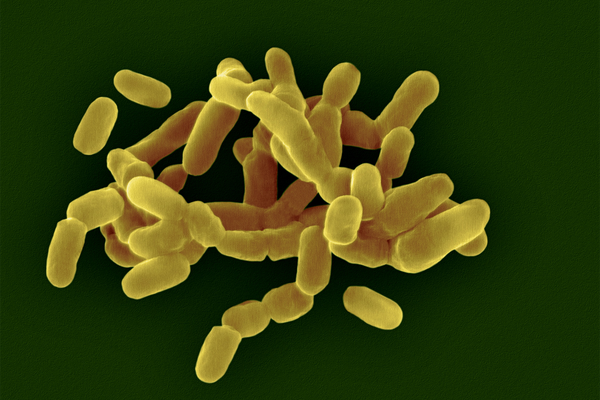

Of the many microbial communities in the human body, the vagina’s microbiome is unique. While increased diversity is key to microbiomes such as those in the gut or mouth, the vagina has been thought to thrive when it has fewer bacterial species overall and more of one particular species crucial to vaginal health, Lactobacillus crispatus.

But a new analysis published last week in Microbiome shows a more complex picture. Of the 28 bacterial species common to the vagina, scientists identified 135 unique combinations of strains of those species, each of which has different functions and cohabits with other strains. “So the diversity exists; we just never had a chance to appreciate it,” says study co-author Jacques Ravel, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and acting director of the Institute of Genome Sciences at the university. The findings show what the different strain combinations may do in the body—and how they could play a role in a person’s susceptibility to sexually transmitted diseases and risk of preterm birth and their overall health.

The microorganisms that colonize the vagina protect against infection. An imbalance of these microbes are associated with certain infections and medical conditions, such as bacterial vaginosis (BV), a painful condition that affects about 30 percent of women between the ages of 14 and 49 in the U.S. Bacterial vaginosis is very ill-defined, Ravel says. While one individual’s infection might present similar symptoms to another’s, including itching and an odorous discharge, “Microbiologically it could be very different,” Ravel says. Past research has identified two specific imbalances of the vaginal microbiota that commonly lead to bacterial vaginosis. In the new study, Ravel’s team sequenced almost 2,000 vaginal metagenomes—the genetic material of all the microorganisms in an environment. This revealed nine communities of bacteria that were specifically linked to bacterial vaginosis.

Some species of Lactobacillus, especially L. crispatus, are known to be associated with a reduced risk of BV. People who have less vaginal L. crispatus may also have a higher risk of acquiring and spreading HIV. The research found many strain combinations of the species that can provide protection from BV. The role of another common species in the same genus, L. iners, is less understood. The new analysis indicated that some women with L. iners were very prone to BV while others were not—the team was able to show that one distinct combination of L. iners strains was more frequently observed in BV cases. This level of understanding could help doctors identify risks of developing the condition based on a specific vaginal microbiome composition, says lead study author Johanna Holm, an assistant professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and a faculty member of the Institute for Genome Sciences.

The study also reaffirmed that a greater diversity of Gardnerella species, other well-known BV-associated bacteria, were linked with the condition. Having lots of different species of Gardnerella and therefore a high number of strains and strain combinations was more related to BV than having fewer species. Other studies have looked into the relationship between Gardnerella strains and bacterial vaginosis but not with as many samples as the recent paper included, Holm says.

People with bacterial vaginosis are typically treated with antibiotics—an intervention that has not changed since the 1980s, says Craig Cohen, a professor in the department of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the paper. It’s unclear why some people experience recurring bacterial vaginosis after antibiotic treatment, but Cohen suspects this may be linked to the presence of different strain combinations contributing to the condition. Holm says the flaws of antibiotic treatment for BV is in part due to the field’s inability to accurately define bacterial vaginosis.

“BV comes in a lot of flavors,” says Melissa Herbst-Kralovetz, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Arizona College of Medicine–Phoenix, who was not involved in the paper. While the new paper is a “great first step” in understanding vaginal bacterial communities and their function, she suggests that more focus is needed on other key BV associated organisms that may play a role in the condition.

Almost three quarters of the study’s participants identified as Black, a population which has a higher risk of vaginal dysbiosis—the scientific term for an imbalance in vaginal microbiota. The findings might be more complicated if other racial and ethnic groups were included at higher percentages, Cohen says. Demographic data such as socioeconomic, household and education information could further improve the interpretation and analysis, Herbst-Kralovetz says.

The researchers are now expanding their current data set to include vaginal microbiome samples from populations that are less studied. The team is also investigating how strain combinations are affected by hygiene practices such as douching and using menstrual products, as well as by sexual behaviors such as using condoms or having multiple partners.

“What our study suggests,” Holm says, is that the severity of BV “may differ depending on what ‘type’ of BV community you have.” Future treatments might be tailored to address these specific community types, she adds. Ravel and Holm hope that a better understanding of the bacterial communities behind BV will help with these kinds of targeted treatment as well as novel diagnosis methods.

Clinicians don’t routinely assess the vaginal microbiome to diagnose BV, Herbst-Kralovetz says. Typically they use Amsel criteria—the current medical diagnostic standard also used in the study—to identify the condition through the presence of lots of thin vaginal discharge, bacteria-covered vaginal cells called clue cells, a fishy odor or vaginal fluid pH levels above 4.5. Sometimes molecular diagnostics that pinpoint BV-associated organisms are used, but these can be difficult to interpret, Herbst-Kralovetz says.

Cohen says such clinical applications could include a self-administered dipstick to test for an optimal balance of vaginal microbes. Early research suggests that probiotics designed to promote growth of good bacteria may also influence the protective abilities of the vaginal microbiome—Ravel’s lab is currently involved in developing probiotic therapeutics for urinary tract infection and BV.

Although the new study was able to identify different strains of bacteria in the vagina more precisely, Cohen says that researchers now need to unpack whether these strain combinations matter to health. “It’s going to take a lot more work to understand the interactions of the microbial and the human metagenome and its effect on health and well-being.”