The number of birthdays you’ve had—better known as your chronological age—now appears to be less important in assessing your health than ever before. A new study shows that bodily organs get “older” at extraordinarily different rates, and each one’s biological age can be at odds with a person’s age on paper.

The new research, published on Wednesday in Nature, identified about one in five healthy adults older than 50 years old as an “extreme ager”—a person with at least one organ aging at a highly accelerated rate, compared with a cohort of their peers. One in 60 adults had two or more organs that were aging rapidly. The study team measured proteins related to organs, including the brain, heart, immune tissue and kidneys. The researchers hope their findings will lead to a future blood test that can pinpoint rapidly aging organs, letting doctors target them for treatment before disease symptoms begin.

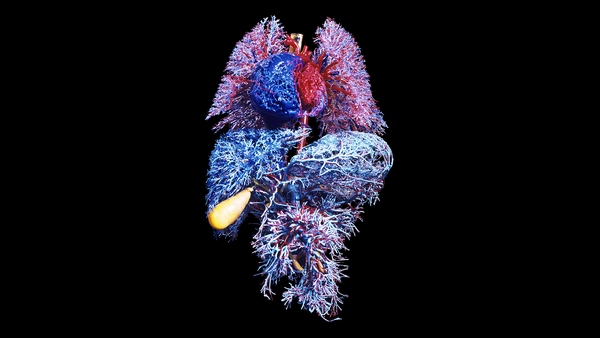

The team sampled the blood of more than 5,500 people, all with no active disease or clinically abnormal biomarkers, to look for proteins that originated from specific organs. The scientists were able to determine where those proteins came from by measuring their gene activity: when genes for a protein were expressed four times more in one organ, that designated its origin. Next the team measured the concentrations of thousands of proteins in a drop of blood and found that almost 900 of them—about 18 percent of the proteins measured—tended to be specific to a single organ. When those proteins varied from the expected concentration for a particular chronological age, that indicated accelerated aging in the corresponding organ.

“We could say with reasonable certainty that [a particular protein] likely comes from the brain and somehow ends up in the blood,” explains Tony Wyss-Coray, a professor of neurology at Stanford University and co-author of the new study. If that protein concentration changes in the blood, “it must also likely change in the brain—and [that] tells us something about how the brain ages,” Wyss-Coray says.

By comparing study participants’ organ-specific proteins, the researchers were able to estimate an age gap—the difference between an organ’s biological age and its chronological age. Depending on the organ involved, participants found to have at least one with accelerated aging had an increased disease and mortality risk over the next 15 years. For example, those whose heart was “older” than usual had more than twice the risk of heart failure than people with a typically aging heart. Aging in the heart was also a strong predictor of heart attack. Similarly, those with a quickly aging brain were more likely to experience cognitive decline. Accelerated aging in the brain and vascular system predicted the progression of Alzheimer’s disease just as strongly as plasma pTau-181—the current clinical blood biomarker for the condition. Extreme aging in the kidneys was a strong predictor of hypertension and diabetes.

Paul Shiels, a professor of cellular gerontology at the University of Glasgow, who was not involved in the new research, says the study was well powered with sizable cohorts. But the age range of the people included was “a little narrow,” he says. “It only looked at older individuals, and it wasn’t representative of a whole life course.”

The measurement of biological aging is an evolving science. “Epigenetic clocks,” a leading approach pioneered by Steve Horvath of the biotechnology research start-up Altos Labs, look at DNA changes to determine tissue age more accurately than other existing biological age estimators. When people age, the body begins to accumulate DNA signatures that can indicate how old a cell or organ is; this allows estimates of age. But epigenetic clocks estimate the age of the whole organism instead of an organ-specific age, Wyss-Coray says.

Other past work by Michael Snyder, a genomicist at Stanford University, has developed “ageotypes” that categorize aging into four distinct pathways: through the kidneys, liver, immune system and general metabolism. Wyss-Coray and his colleagues’ work expands these aging pathways to more organs and body systems.

Wyss-Coray anticipates this research could lead to a simple blood test that could guide prognostic work—in other words, a test that could help foretell future illness. “You could start to do interventions before that person develops disease,” he says, “and potentially reverse this accelerating aging or slow it down.”

This research is part of the growing field of personalized diagnostics, which is based on the idea that several biological indicators of organ health can help clinicians target treatment. Blood measurements have traditionally been used to identify illness in the body, with clinicians making a diagnosis only after a person crosses the threshold of a certain set indicator. But as protein markers become more sensitive, “you can actually detect something abnormal before you have clinical manifestations,” Wyss-Coray says. He and his colleagues integrated this research into a recently filed patent tied to their start-up company Teal Omics, which focuses on precision medicine through biomarker testing.

Some companies, mostly based in California, already offer blood, urine or saliva testing that purports to determine one’s overall biological age. The momentum of commercial epigenetic testing is a “gold rush,” Shiels says. “There is a degree of oversell on what [the tests] can do.”

A single organ doesn’t tell the whole story of aging because deterioration processes are interconnected and affect an entire organism. “We understand a lot about the aging process on sort of a micro level,” Shiels says. “But a lot of the factors that drive age-related organ dysfunction are environmental. So it’s lifestyle, pollution, what you eat, microbes in your gut.”

According to Wyss-Coray, each organ is fundamental to overall health. He likens the human body to a car: “If one part doesn’t work well, the other parts start to suffer,” he says. “If you maintain certain parts, you can prolong the life span of the car.”