A new planetary report card confirms that humans are making little progress on confronting the climate crisis.

“Humanity is failing, to put it bluntly,” says Bill Ripple, an Oregon State University ecologist. “Rather than cutting greenhouse gas emissions, we’re increasing them. So we’re not doing well right now.”

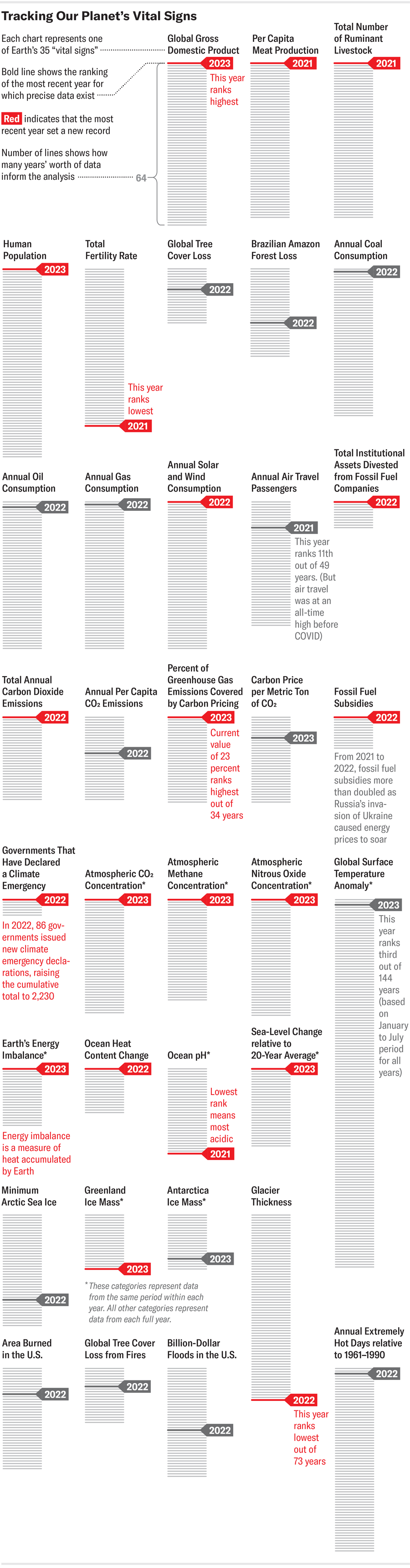

Ripple is co-author of research published on October 24 in BioScience that offers a snapshot of Earth’s status on 35 “planetary vital signs” with regards to climate. The analysis shows that humans have reached new extremes on 20 of these measurements, including global gross domestic product, fossil fuel subsidies, annual carbon pollution and glacier thinning. Overall, the report considers human activities, such as deforestation and meat consumption, as well as the planet’s responses to those activities, including characteristics such as ice loss and temperature changes.

Ripple also says that in addition to the 35 formal variables, most of which he and his colleagues began to track in late 2019, the team is closely watching global estimates of populations that are experiencing undernourishment. Though undernourishment can have political causes, it is often tied to climate factors such as droughts and floods that damage crops.

Where possible, the analysis is based on data through the present, although some variables without freshly reported measurements rely on slightly older data. But there’s no denying that the picture is grim. “Many climate-related records have been broken by enormous margins in 2023,” Ripple says. For example, July was the hottest month ever recorded, and September was the most anomalously warm month, both by a significant amount.

The researchers also noticed a steep increase in global disasters tied to climate, including flooding, wildfires, heat waves and landslides. Ripple and his colleagues identified 14 disasters since October 2022 that were “definitely” or “likely” exacerbated by climate change. For example, a separate analysis found that heat waves that baked parts of North America and Europe this summer would have been “virtually impossible” without climate change. All told, these disasters killed thousands of people and affected millions; several individual events caused more than $1 billion in damage. In fact, the U.S. has already set a record for “billion-dollar disasters” this year, with several months left.

“What we’ve been noticing is that as temperatures are creeping up, climate-related disasters are leaping up,” Ripple says. “We’re getting this big surge in climate disasters.”

Even more concerning, he says, is that many of these disasters are hitting communities that have historically produced very little carbon pollution. Although the U.S. has been hit by extreme heat and wildfires, South America and Southeast Asia have also sweltered, while Libya and northern India have seen extreme floods. “The less wealthy countries that had little to do with creating climate change are having the most vulnerability to the climate disasters,” Ripple says.

Because of that, the report highlights the importance of confronting the climate crisis with justice in mind—a key aspect of this kind of work, says Joyeeta Gupta, a sustainability scientist at the University of Amsterdam, who was not involved in the new research. “We are repeating ourselves over and over again about the nature of the problem and the impacts,” Gupta says, noting that scientists have known for decades that the climate is changing because of human activity.

“Natural scientists very often don’t include justice issues,” she adds. “I think it’s really important that we bring this justice issue much more centrally to our narrative because otherwise we won’t solve these problems; we’ll just keep telling people that there are problems.”

Although many factors Ripple and his colleague studied are complex and difficult to tackle individually, not all are. For example, the team highlights that government subsidies of fossil fuels were at their all-time high in 2022, the most recent year out of the 13 for which data are available. The researchers cite Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 as a destabilizing factor that prompted the steep increase that more than doubled subsidies over their previous level. “Governments are subsidizing the fossil fuel industry, which seems a little counterproductive,” Ripple says. “Immediately, we can’t do a lot to stop the disasters, but we do have a lot of control over these subsidies.”

Without rapidly shifting away from fossil fuels and toward renewables, the concentration of carbon dioxide will continue to rise in the atmosphere, causing sea levels to continue to rise, ice to melt, more heat waves to occur and oceans to become more acidic.

Fortunately, Ripple and his colleagues have found that humans have made progress in developing wind and solar power. In another positive note in the report, deforestation globally and in the Amazon—a particularly vital region for climate—has decreased.

Ripple’s 35 “vital signs” are just one of several frameworks that scientists use to understand how the planet is changing as the climate crisis unfolds. A separate project announced last month that humans have crossed six of nine planetary boundaries beyond which it becomes difficult to support the societies our species has built. The boundaries include variables, such as biodiversity and nutrient flow, that are not included in the new analysis, as well as some of the vital signs, such as deforestation and ocean acidification.

Ripple says he hopes that policymakers and citizens take the analysis seriously. “Life on planet Earth is under siege,” he says. “Whether you look at planetary boundaries or our planetary vital signs, it’s telling a similar story in that this is going to take major attention by humanity and big changes.”