On November 1 a NASA spacecraft called Lucy will introduce humans to a world called Dinkinesh—nicknamed Dinky—the smallest main-belt asteroid we’ve ever seen up close.

Lucy launched in 2021 to explore a mysterious group of asteroids called Jupiter’s Trojans. These space rocks orbit the sun at the same distance as Jupiter in two clusters: one cluster races ahead of the gas giant while the other trails behind the planet. All told, scientists know of more than 12,000 of these objects in Jupiter’s orbit, and they think this eclectic group of primitive space rocks could help decode the solar system’s early history. Hence Lucy will zip past six of Jupiter’s Trojans beginning in 2027.

“The goal of Lucy is to understand the diversity of Trojans,” says Hal Levison, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado and principal investigator on the Lucy mission. “In order to do that, you need to visit lots of objects, which is what we’re doing, and in order to do that, you need to be hauling ass.”

Lucy is moving so quickly that the mission’s primary science observations total just 24 hours spread across the spacecraft’s 12-year trek around the solar system, Levison says. The mission is only flying past its targets, not making extended stays—and once the probe has left an asteroid, that’s it. “There’s no going back; there’s no do-overs,” he says.

So when mission personnel realized that as Lucy trekked through the outer solar system, it would fly within 40,000 miles of a small, then nameless asteroid, they decided to detour for a dress rehearsal and nudged the mission’s trajectory to pass just 280 miles from the tiny body. Because of Dinkinesh’s alignment with the sun and the spacecraft during the flyby, the maneuver will better mimic future planned Trojan flybys than the mission’s original first target, another main-belt asteroid Lucy is set to encounter in 2025.

(The Lucy mission takes its name from an ancient hominin fossil found in northern Ethiopia that suggested that some 3.2 million years ago, early human relatives were walking on two feet; in Amharic, the fossil is called Dinkinesh. The spacecraft’s 2025 target, asteroid Donaldjohanson, is named for the paleoanthropologist who led the excavation that unearthed Lucy in 1974.)

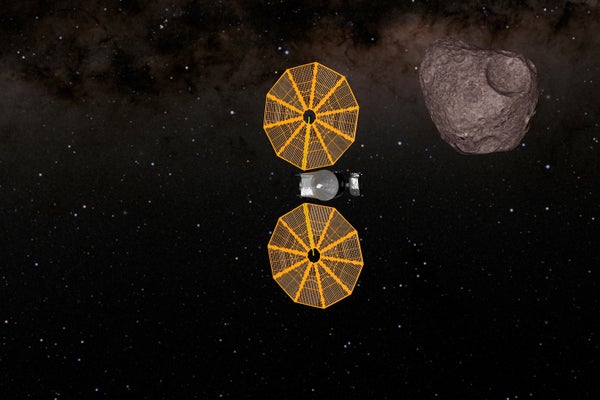

In addition, Lucy’s science team has more cause for anxiety about the flybys than it would have hoped. During the months following Lucy’s launch, spacecraft personnel struggled to fully unfurl one of the probe’s two circular solar arrays before eventually concluding the mission was okay to proceed just shy of fully locking the array in place. The spacecraft’s good performance during a flyby of Earth last fall validated this decision, but the unlatched array could cause the spacecraft—and its instruments—to shake more than planned while performing flyby observations, potentially lowering the quality of Lucy’s data. Testing the procedure on Dinkinesh will give the team enough time to adjust the probe’s approach to each Trojan target if needed to ensure sharp images and measurements.

So for Lucy, Dinkinesh is first and foremost an engineering test and a practice run. But planetary scientists—who never turn down an opportunity to see something new in the solar system—are excited for their glimpse of the little space rock.

“The science is a bonus, but bonus science is always really interesting in my experience,” says Jessica Sunshine, a planetary scientist at the University of Maryland and a Lucy co-investigator. “Collectively, in planetary science, we’ve never flown by an object and went, ‘Eh, well, that was kind of boring.’”

When Dinkinesh was formally added to Lucy’s itinerary earlier this year, scientists knew only its location and unimpressive size. “We knew it was kind of small—but nothing else, actually,” says Julia de León, a planetary scientist at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands who is not on the Lucy mission but helped coordinate some preparatory peeks at Dinkinesh. “So we all did our best,” she says, with astronomers hustling to telescopes to learn more about the asteroid.

Thanks to those efforts, scientists now have a somewhat better picture of Dinkinesh, which is shaping up to be an intriguing little space rock: rich in silica, roughly oblong and sedately spinning, with an estimated diameter of circa 900 meters and a day about twice the length of Earth’s 24-hour diurnal period.

In the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, scientists have only visited much larger space rocks, such as the Dawn mission’s targets, the asteroid Vesta and the dwarf planet Ceres, which are among the largest known objects in the belt. Both are hundreds of times larger than Dinkinesh. “It is by far the smallest thing we’ve ever seen in the main belt,” Sunshine says of Lucy’s tiny target.

Dinkinesh appears similar in scale to a few near-Earth asteroids that spacecraft have recently seen up close, however. These include carbon-rich Bennu, samples of which NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission recently delivered to Earth, as well as Didymos, which NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission zipped past on its way to impacting the asteroid’s small moon, Dimorphos.

Comparing Dinkinesh and Didymos should be particularly interesting, Sunshine says, because the two asteroids are made of the same type of material type and are similar sizes, just in different locations. “It’s rare that we get to have that sort of direct comparison in our line of science, so I was very excited when this became an obvious flyby target for Lucy,” she says.

Such a direct comparison is particularly valuable because scientists believe that near-Earth asteroids hail from the main belt, having been kicked deeper into the solar system by past gravitational perturbations. So scientists hope that Lucy’s glimpse of Dinkinesh will help them understand the changes main-belt asteroids undergo as they transform into near-Earth asteroids. “It will be like studying a near-Earth asteroid at its source region, where it’s generated,” de León says.

Lucy’s flyby of Dinkinesh will firm up scientists’ preliminary estimates of the asteroid’s basic shape and composition and will also allow them to count craters on its surface to better calibrate its age. And specific science questions aside, asteroid experts are just excited to see another of the solar system’s space rocks snap into focus.

“It’s going to be amazing to see those [images] come down,” Sunshine says. “It doesn’t get old; I’ll tell you that much.”