NONFICTION

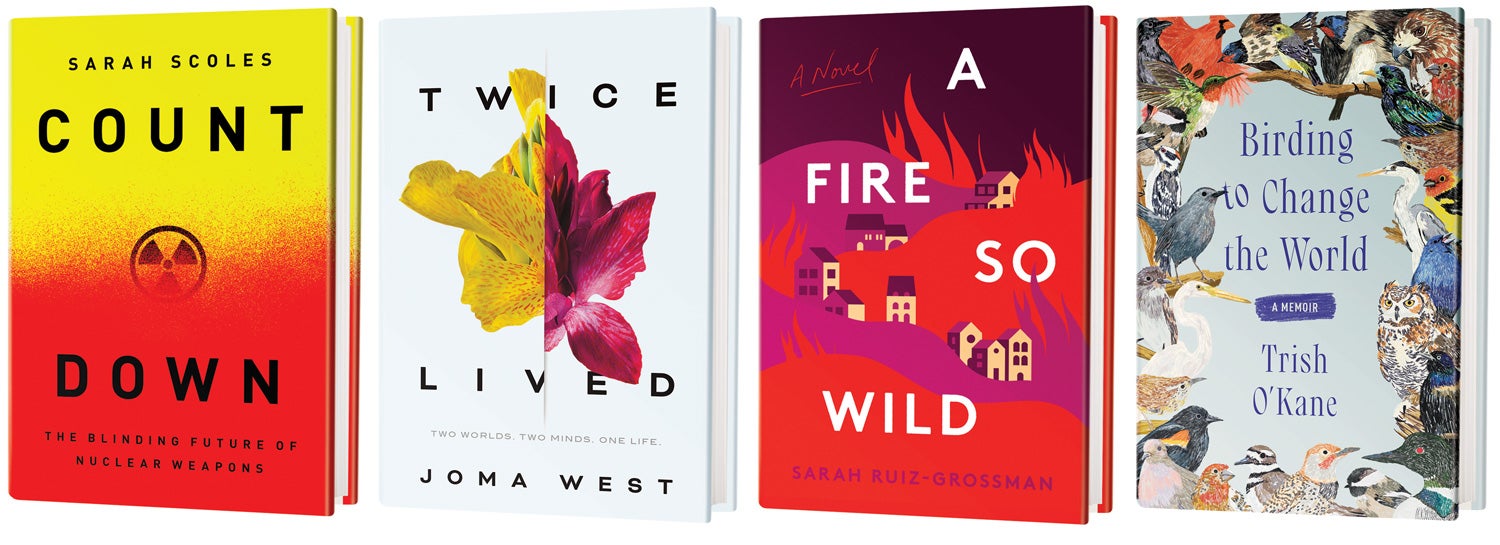

Countdown: The Blinding Future of Nuclear Weapons

by Sarah Scoles

Bold Type Books, 2024 ($30)

The central premise of Sarah Scoles's fascinating new book is at once straightforward and disconcerting: the U.S. is in the middle of a massive refurbishment campaign to upgrade its geriatric nuclear arsenal—and yet nobody, not even the people charged with that task, knows precisely how these weapons operate. The inner workings of the most destructive thing human beings have ever built remain, in large part, a mystery.

From that starting point, Scoles, who is a contributor to Scientific American, ventures on a kaleidoscopic interrogation of the weird, secretive fraternity that is America's nuclear sector. Traditionally, it's not a particularly well-explored space, despite our recent, Oppenheimer-fueled obsession with all things atomic. The reality of modern nuclear-weapons work is at once much less spectacular and much more intricate than one might imagine—an entire alphabet of acronymic agencies responsible for everything from cleaning up radioactive spills to conducting CSI-style investigations of hypothetical dirty-bomb detonations.

At its most interesting, Countdown is an exploration of uncertainty in a field whose awesome destructive capacity makes uncertainty a deeply worrying thing. Because of bans on aboveground nuclear testing, the traditional method of figuring out how nuclear bombs work—namely, blowing them up—isn't feasible anymore. So scientists are left with computer models and other esoteric techniques to try to figure out, for example, how the radioactive matter in nuclear bombs changes over many decades in storage.

The weakest part of the book is, unfortunately, outside of Scoles's control. Few facets of government work are as heavily classified as the nuclear program, and as a result, many anecdotes and narrative threads come to a hard stop not at any satisfying conclusion but rather when the documentary trail becomes inaccessible or when an interview subject turns reticent.

Nevertheless, Scoles does get at the heart of the many paradoxes that frame the nuclear age. The people she speaks to—some of them inspired to do this work because they believe that nuclear weapons are a means of deterrence, a means of making the world safer—are clearly engaged in their own internal struggles with self-doubt. In this way, a book chronicling the stewards of our deadliest weapons of war becomes, at times, the story of people at quiet war with themselves. —Omar El Akkad

In Brief

Twice Lived

by Joma West

Tordotcom, 2024 ($26.99)

Joma West's urgent, slice-of-life novel imagines a reality where, from the womb and into adolescence, some children “switch” at unpredictable intervals, vanishing into a parallel world, leaving behind their selves, names and families until they switch back. At some point they settle into a single existence. This moving book explores how different upbringings can yield different selves, centering on one teen—Canna in one life and Lily in the other—and her mother in each place, both of whom fear the next switch might mean Canna/Lily never returns. As each iteration of the protagonist strives to stay in the world she loves, West's brisk, chatty scenecraft proves as resonant emotionally as the premise is conceptually. —Alan Scherstuhl

A Fire So Wild: A Novel

by Sarah Ruiz-Grossman

Harper, 2024 ($25.99)

Sarah Ruiz-Grossman presents a passionate yet critical observation of the devastating effects of a California wildfire that indiscriminately upends the lives of residents from various socioeconomic backgrounds. Wealthy Abigail organizes fundraisers for low-income housing, but now finds her own house reduced to ashes. Sunny, a homeless construction worker, was promised one of the new apartments, but the fire puts that on hold. Middle-income high school teacher Gabriel and his ex-wife search for their teenage daughter, who was with Abigail's son during the blaze. Ruiz-Grossman's piercing commentary reveals the inequality and injustices of climate change for people just trying to live their lives. —Lorraine Savage

Birding to Change the World: A Memoir

by Trish O'Kane

Ecco, 2024 ($29.99)

Struggling to cope with the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Trish O'Kane becomes an “accidental birder” when her connection with a single cardinal opens her eyes to the hope and healing of bird-watching. As a Ph.D. student and passionate amateur ornithologist in Wisconsin, O'Kane attempts to defend the local bird populations against constant threats by emulating the birds themselves: a starling murmuration, a chevron of geese, a squawking flock of mobbing crows represent “avian attributes, talents, and skills our species urgently needs.” Fascinating revelations (even about the humble sparrow) punctuate this thoughtful discussion of complex birding issues such as wildlife management and environmental justice. —Dana Dunham