Last year more than 4,500 children and teenagers were killed by gunfire in the U.S., and many more were injured. That harrowing statistic made 2022 the third straight year that guns were the leading cause of death for those under the age of 19 in the country—after such deaths overtook fatalities caused by motor vehicle accidents in 2020.

These statistics are just “the tip of the iceberg of the larger epidemic,” says Zirui Song, who studies health care policy and medicine at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital. In a new analysis published in November in Health Affairs, Song and his colleagues quantify the devastating and often invisible ripple effects of a firearm injury on children and their family. The team’s results show that in the year following a young person’s gunshot injury, psychiatric and substance use disorders soar and cost the health care system a substantial amount.

“The cruel reality is that survivors face a challenging, daunting, painful [and] often lonely road to recovery that receives very little attention,” Song says.

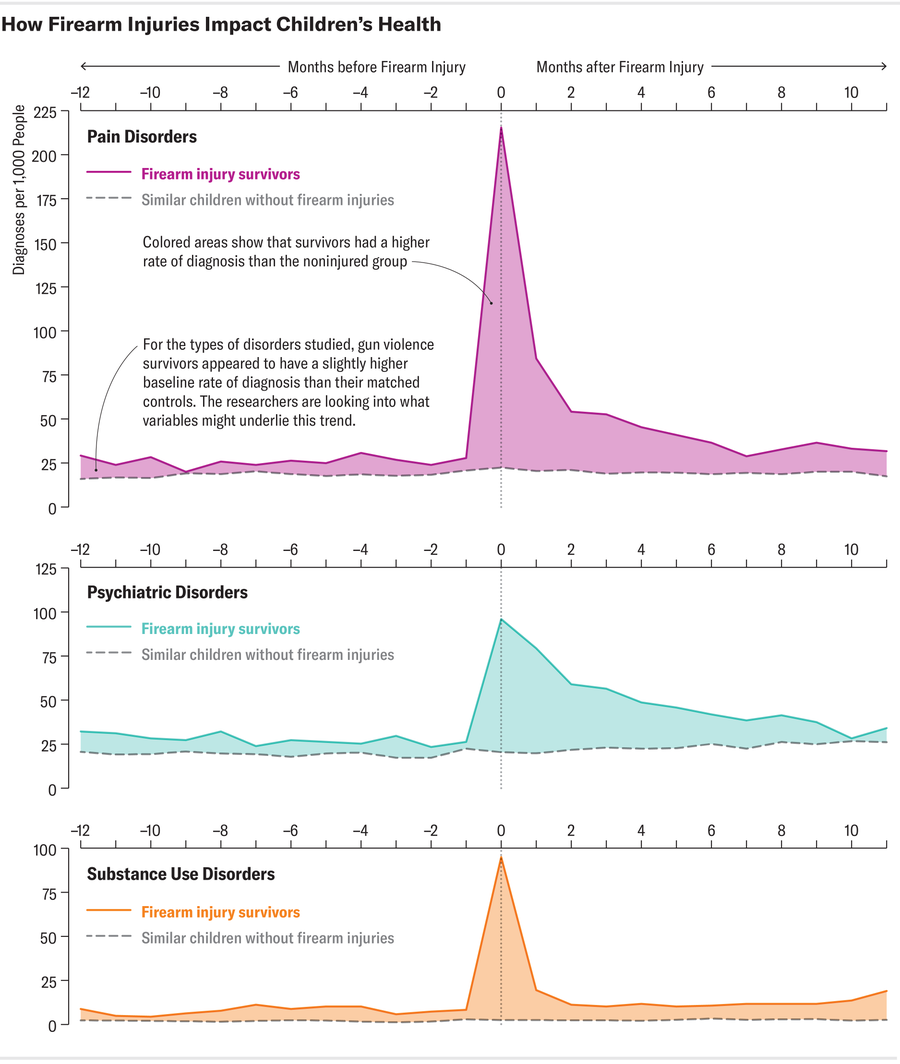

Song and his colleagues examined employer health insurance claims data from 2007 to 2021 to compare more than 2,000 young gun violence survivors with about 10,000 matched controls who had no firearm injuries. In the year following the shooting, the prevalence of substance use disorders and pain disorders more than doubled among the group of young survivors of gun violence, who were up to 19 years old. The survivors also had a 68 percent increase in psychiatric disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder after the time of the shooting relative to the control group. The effects were worse among those with more severe injuries. These results mirror similar research by Song’s team on adult survivors of gun violence, which found increased rates of in mental health disorders and increased health care spending after the injury.

Firearm injuries can affect a young person’s life and mental health in many ways, explains Lauren Magee, an expert on gun violence and its impact at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis, who was not part of the study. From her own research, which has involved speaking with survivors of gun violence, she says that the psychological distress experienced by survivors can manifest as hypervigilance of one’s surroundings and a fear of going out in public. But it can also have the reverse effect by making survivors “feel like they’re invincible, which can be harmful,” Magee says. This can lead to engaging in riskier behaviors, such as drug use.

Families of survivors are also impacted by the injury, the researchers found. Parents experienced a 30 percent increase in psychiatric disorders, with sharper increases among those whose children experienced more severe injuries. Mothers and siblings of survivors also saw their doctors for routine medical care less often than before the shooting. “The whole family is a survivor of the firearm injury,” Song says.

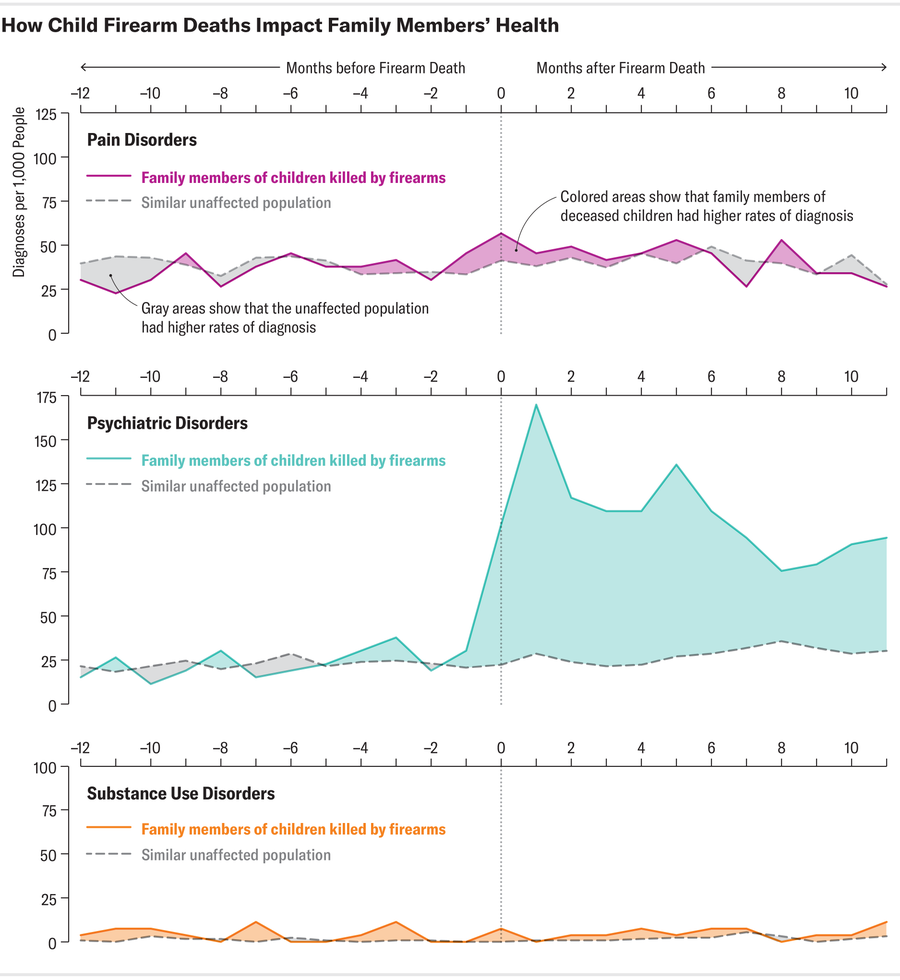

This effect was magnified among families whose children were killed by firearms. Parents in that group experienced twofold to fivefold increases in psychiatric disorders—compared with an increase of 1.3-fold among survivors’ parents.

These findings illustrate that a shooting doesn’t end when the smoke clears and the gun has been fired, says Daniel Semenza, director of interpersonal violence research at the New Jersey Gun Violence Research Center at Rutgers University, who was not involved in the study. “Somebody like me spends every day of their life looking at shooting data and homicide data,” Semenza says. “If you’re not careful, you quickly lose sight of what this actually looks like in people’s lives and what the burden truly is.”

Shootings also take a high financial toll. Health care spending on survivors increased by an average of about $35,000 per person annually, which accounted for mental health services, imaging, lab tests and home care, among other costs. That figure represents actual transacted prices—95 percent of which were paid by insurers or employers—instead of hospital charges that were not yet negotiated with a health insurance provider. The latter metric was often used in previous analyses, according to Song.

“Society, at the end of the day, foots a rather large bill for the survivors and family members of youth gun violence,” Song says. “Ultimately, health care spending in this population comes out of workers’ wages.”

The rise in disorders that was documented in this analysis is also likely to be an undercount because it does not include populations that are insured by Medicaid or Medicare or those without insurance. These groups are among the most vulnerable to gun violence and are at a higher risk of many mental and physical health conditions because of poverty and limited access to the health care system, Semenza says. Gun deaths also disproportionately affect communities of color. Song’s team hopes to conduct future analyses with government health care data to quantify the longer-term effects of gun violence across different demographics.

And while this analysis captured data for one year following a shooting, the health effects of gunshot injuries can be lifelong. “The journey of surviving is years, if not decades, long,” Magee says. For family members, especially those that that have experienced the death of a child, it can sometimes take longer than a year to process that they even need to talk to a mental health care provider about the death, for example.

In a country that has so far experienced, on average, about two mass shootings (those that injure or kill four or more people) per day in 2023, these results show the sprawling effects on community health that go beyond the number of injuries and fatalities. Gun violence “shapes well-being across the entire population,” Semenza says. With this new understanding of what it’s doing to children and adults, “we have to take that seriously,” he says, “because we are at unacceptable levels of shootings—and we have been for many decades now.”

Editor’s Note (1/8/24): This article was edited after posting to better clarify the figures for the survivors’ increase in psychiatric disorders a year after the shooting and the average increase in annual health spending on survivors per person.

A version of this article entitled “The Invisible Toll” was adapted for inclusion in the February 2024 issue of Scientific American.