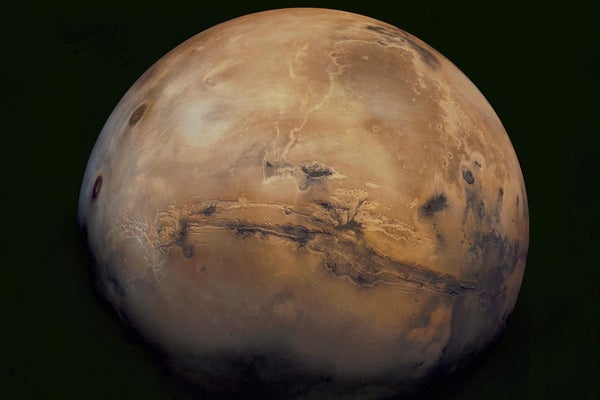

In September NASA’s Mars Sample Return (MSR) independent review board (IRB), led by the agency’s former “Mars czar” Orlando Figueroa, released findings and recommendations about the MSR project, a collaboration between NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) that means to return the first samples from the Red Planet. The IRB members did a terrific job analyzing, in their words, the “near zero probability” of its current plans and budget succeeding.

Mars Sample Return matters to our nation and space program and to science, the board emphasized. The return of carefully selected samples, such as ones weathered by geothermal vents, as well as sedimentary and aggregated rocks, will allow scientists on Earth to extensively examine their geochemistry and microscopic composition. It could possibly reveal signs of life, or at least the ingredients of life, on Mars. The mission therefore directly addresses the principal question of space exploration—the nature of life in the universe. But the report’s key finding makes it clear that the mission needs a stretched-out, more robust architecture that would delay its launch into the 2030s and the return of samples to the mid- or even late 2030s. “The current MSR architecture is highly constrained and is not sufficiently robust or resilient,” the panel said in its report. NASA’s current sample-return mission plan relies on the aging Perseverance rover, launched in 2020, to collect its samples. A second rover from Europe was planned, but its development was cancelled. There is a backup plan in case Perseverance is not working, but it relies on brand-new helicopters doing something novel: picking up and carrying the samples. A delay and stretch-out of the schedule will make the rover older when it is needed and move the mission into less favorable trajectory opportunities in the 2030s. That raises the cost and risks of the mission and lowers its chances for success. The report concludes, “Other [return mission] architectures may be more robust and more resilient to schedule risk.”

In other words: back to the drawing board. If NASA and ESA continue with MSR (and the report strongly recommends that they should), then a more robust plan involving the collection of more samples and including additional hardware (possibly another rover) must be devised. This plan would stretch well into the 2030s. The panel also noted China’s development of its own, much simpler Mars sample-return mission for 2028 or 2030, which is likely to bring samples back to Earth several years before the NASA-ESA mission returns. (The Chinese mission is more of a “grab sample” mission, in which a lander takes samples from the immediate vicinity of its landing site, and it is much shorter in duration than the NASA-ESA one.) This need not be a negative. We can make the most of our more robust mission by engaging with a putative rival. This will allow us to serve diplomacy while serving science.

According to the report, the NASA-ESA plan is much better scientifically. It will be able to obtain many more extraordinarily well-selected samples, based on both years of in situ experience from previous missions and a careful and extensive sampling campaign by the Perseverance rover. The sampling will be far more wide-ranging than that of the Chinese plan, which is limited to one small region around the mission’s landing spot. Nevertheless, it would be beneficial for American and European scientists to be able to analyze a bit of those first samples—both to uncover the intrinsic science they contain and to exercise the extensive plans of the NASA sampling procedures. Similarly, Chinese scientists would benefit enormously if they had some access to the NASA-ESA samples. A sample exchange would benefit both the U.S. and China. And therein lies the opportunity.

Examining each other’s samples poses no conceivable strategic threat to either country—the likelihood of a microscopic secret inside a Martian rock helping either nation in their military or economic competition is around zero. But cooperating on this Martian investigation could build up a benign and positive scientific relationship that would serve both countries. It would add to our exploration of Mars, and there are no downsides to advancing China’s exploration of Mars. It plays into American strength—our vigorous and successful science experience on Mars—and mitigates the more trivial worry about who will conduct a Mars sample-return mission first. And it provides resiliency to further delays or mission problems.

One obstacle would be reluctance springing from a 2011 law barring even the barest NASA cooperation with China without FBI approval. Exchanging samples involves no dangerous interactions with sensitive hardware or software. But this draconian law has so inhibited agency scientists that one privately told me that they were reluctant to even have a cup of coffee with Chinese researchers at space events. The policy allows the U.S. to cooperate in space with Vladimir Putin while ruling it out with the world’s other leading economy. That might suggest that we need to rethink it.

China and the U.S. are at an impasse right now—one filled with hostile, mistrusting, edgy geopolitics. Space cooperation among rivals has a distinguished history. Even now, the U.S. and Russia cooperate on the International Space Station, and in the middle of the cold war, we exchanged lunar samples from the Apollo and Luna missions. Moreover, neither the U.S. nor China want to let current foreign policy tensions move toward confrontation. Presidents Joe Biden and Xi Jinping have expressed interest in developing cooperative initiatives, and in the past three months several U.S. Cabinet officials have gone to China to seek such initiatives. Mars certainly could provide one consistent with the long history of international cooperation in space that would support peace and geopolitical stability.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.