Gison Morib was home lying in bed, sick from exhaustion after a month-long jungle expedition, when his phone buzzed and a black-and-white photograph appeared. Morib ran outside, jumped on his motorbike and sped through the city of Sentani on Indonesian New Guinea to his colleagues’ expedition and research base—where he broke down in tears. “I cannot believe we found it,” was all he could say, over and over. The photograph showed the first recorded sighting in more than 60 years of an Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna, an egg-laying mammal. After the researchers had spent three years of research and four weeks of trekking through the island’s remote Cyclops Mountains—and after one leech attaching itself to Morib’s eyeball—the team’s camera trap had finally captured an image of the echidna. “Even now I can’t describe the feeling [I had] when we got it,” says Morib, a biology undergraduate student at nearby Cenderawasih University. “I cannot describe the goodness of God.”

It can be painful for scientists to conclude that an entire species is gone forever. So after at least a decade without recorded sightings, local researchers sometimes simply declare a species temporarily “lost”—hoping it may eventually be found again—instead of giving up entirely. In 2023 that hope led to rediscoveries of animals that included Attenborough’s echidna, De Winton’s golden mole in South Africa and the Victorian grassland earless dragon, a type of Australian lizard that went unseen for half a century. Such hope also fuels ongoing, decades-long searches for species such as the American Ivory-billed Woodpecker, which was last seen in 1944.

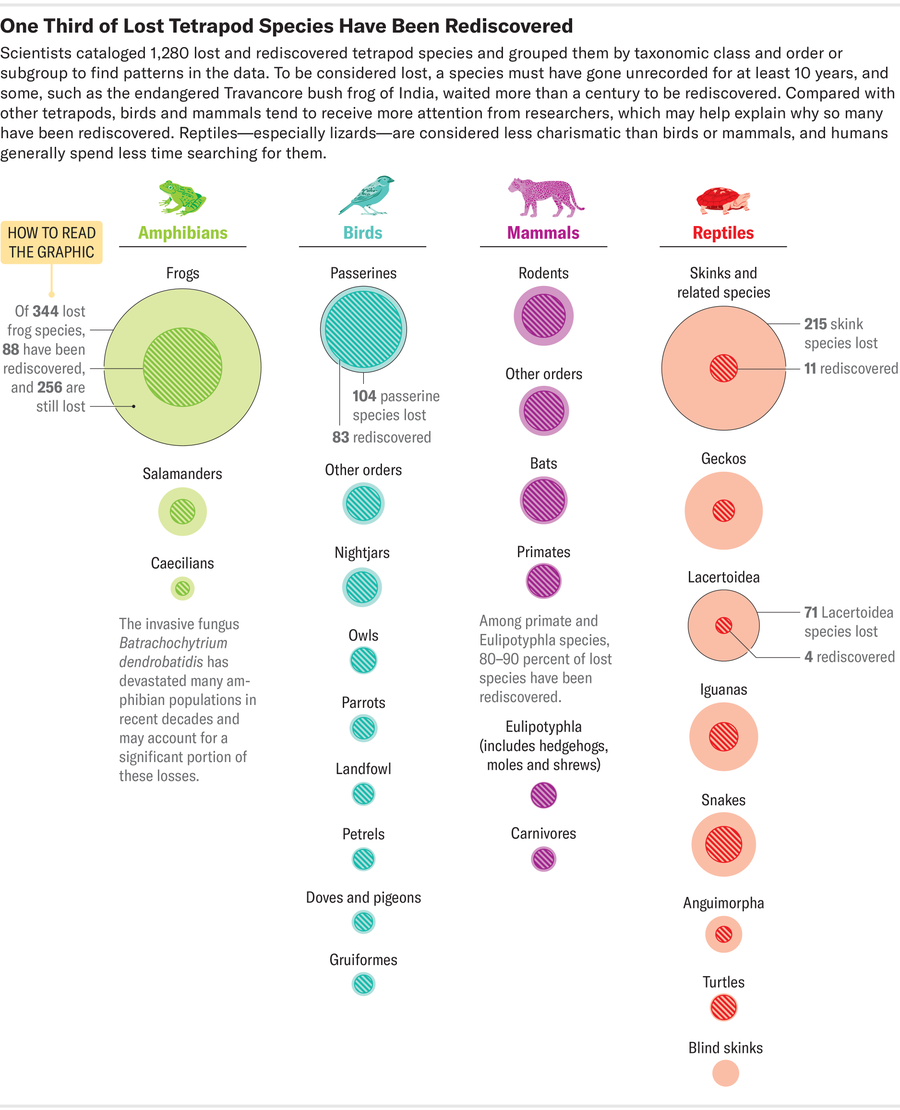

Now an international study published on Wednesday in Global Change Biology aims to “bring a bit of science back to the search” for all mammals, amphibians, reptiles and birds playing hide-and-seek, according to senior study author Thomas Evans, a conservation scientist at the Free University of Berlin. In a span of two years, Evans and a team of researchers across the globe—from the U.S. to China, Ecuador and South Africa—compiled what they call the most exhaustive catalog ever of four-limbed creatures that were considered lost to science and those among these animals that were later rediscovered.

For Evans, the project started years ago when he read “a huge, great, really depressing book” called Extinct Birds by paleontologist Julian P. Hume. He says that the book also came with a sliver of hope and a spark of inspiration in the form of an appendix listing lost species that have been rediscovered. Although there has been plenty of research into lost species, the study authors say that rediscoveries haven’t been thoroughly assessed since 2011. Analysis tallying losses and rediscoveries across animal groups is even rarer, Evans says.

His team’s catalog suggests that 856 species are currently missing and that the number of lost species is growing around the world faster than expedition parties can keep up. And this is occurring even though researchers are finding animals through the use of increasingly sophisticated technology, including systems that detect environmental DNA (eDNA) traces of burrowing birds near the South Pole, software that disentangles the noises of different nocturnal species, and even techniques used to spot microscopic traces of rare frogs in ship rats’ stomachs.

Adding up losses and rediscoveries also suggests that roughly a quarter of lost species are likely already extinct. “It’s kind of sad to think,” Evans says, “but as far as we’re concerned, people aren’t going to find them.” Analysis shows that many rediscovered species fit a certain profile: they are big, charismatic mammals or birds that tend to live across a range of habitats, often near humans and in more-developed countries. So, Evans says, if an animal fits the bill for the kind of species that is usually found more easily but continues to evade researchers after long searches, it is probably gone forever. The thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, is a good example: since the last captive thylacine died in a zoo in 1936, the wolflike species has taken on huge cultural significance across Australia and inspired decades of searching, but it remains lost. The paper argues that precisely because the thylacine is a perfect candidate for rediscovery, the fact it remains lost strongly suggests that it is actually extinct. The same goes for more than 200 other lost species that have been thoroughly searched for as well, Evans says.

On the other hand, creatures that don’t fit the profile for easy rediscovery, especially reptiles, could still be out there. Because they’re often hard to find and inspire less search effort, small, uncharismatic species are more likely to genuinely be lost but still alive, Evans says. His optimism is backed up by the numbers: new species of small reptiles continue to be discovered at a steady rate, and rediscoveries have boomed, with more than twice as many lost reptiles found between 2011 and 2020 than in the decade before.

The thylacine has acquired a Bigfoot-like status, complete with amateur hunters and highly questionable sightings. Meanwhile reptiles such as the Fito leaf chameleon of Madagascar are probably sitting pretty and waiting to be found. (Scientists haven’t yet reobserved this chameleon, partly because the French explorers who first described it in the 1970s named it “Fito”—a locally common place name that covers vast areas. No one knows where its exact range is, and few have looked.)

A probability analysis of some factors also rang “alarm bells” in different ways for different classifications of lost species, Evans says. Mammals classified as lost on islands, such as the Bramble Cay melomys, a rat lost in 2009 and declared extinct in 2016, are disproportionately likely to be gone for good, compared with mammals in other environments. There’s also a sweet spot for finding birds after they’ve been lost: 66 years, on average. This time span is long enough to raise interest in search expeditions but not so long that the animals are considered extremely likely to be extinct. So the odds are not good for the more than a dozen bird species that were lost more than a century ago.

Evans hopes such details about what may be simply unseen versus what is more likely extinct will help conservationists like Christina Biggs, who has been curating a list of 25 “most wanted” species for Texas-based charity Re:wild since 2017. “We have limited resources, and we have to make hard decisions on where to put that money,” says Biggs, who is also one of the new study’s 26 co-authors. “We want to prevent the most extinction we possibly can. [Evans’s] research helps to direct us.” Re:wild is currently using the study’s findings to update its 2024 search lists.

But is finding a lost species always in its best interest? After a rediscovery, it can take months to secure an area from poachers or tourists. The researchers who spotted the Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna still have not revealed exactly where they found it. “In publicizing something you’ve rediscovered, you’re publicizing a food source for hunters,” says biologist James Kempton, who led the expedition that found the echidna and was not involved in the cataloging study. Morib notes that in a dialect of Tabla, the local language, the name for the echidna, amokalo, contains a word for “fat” because of the animal’s desirable taste.

Biggs, though, notes that rediscoveries often galvanize concrete action. “As soon as they’re rediscovered, they go into a pipeline to have designations made possible: ‘protected areas’ or ‘marine protected areas,’” she says. “So everything that we do could potentially save an entire other body of species in that same habitat. To me, that’s a very hopeful thing.” For instance, when the call of the Blue-Eyed Ground Dove was heard in 2015 in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais, north of Rio de Janeiro, for the first time in 75 years, it sparked the creation of an 89,000-acre state park. Evans adds that for some of the most elusive species, researchers could use the study to decide if a creature is likely still alive—and then draw broad protected areas around its general region rather than send possibly fruitless expeditions to the area to prove the animal’s existence.

With each extinct species, humans can lose something ecological and cultural. Across the Cyclops Mountains from Morib’s hometown of Ilu the Yongsu Sapari community used echidnas as a “peace tool” to arbitrate disputes. “If brothers or friends fought, they had to find an echidna,” Morib says—a solution that would be increasingly difficult. The Hawaiian Crow, extinct in the wild, was thought to carry lost souls to their resting place. Now, outside of captivity, its call is only heard when Indigenous priests repeat a crow-like chant during traditional prayers. “Everything is connected,” Biggs says. “Every single species does matter. It behaves in an ecosystem and fulfills a purpose within it that then underpins all of the life that we have on Earth.”