LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

[New to Lost Women of Science? You can listen to our most recent episode of Lost Women of Science Shorts here and our most recent multiepisode season here.]

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

Ruth Howes: We wrote the book to tell their stories, and that was our hope: we'd make sure they were not lost.

Katie Hafner: This is Lost Women of the Manhattan Project, a special series of Lost Women of Science. I'm Katie Hafner.

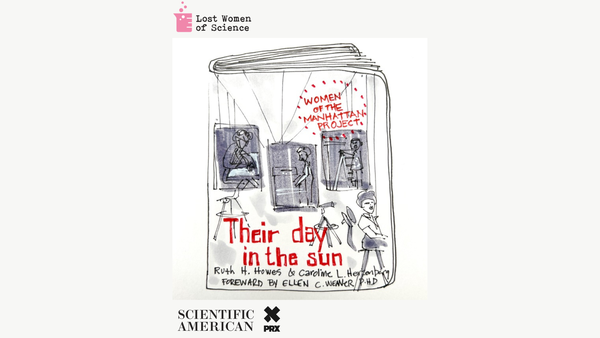

For the past few weeks, we've been bringing you stories of women who worked on the top secret project to build the atomic bomb that would end World War II in 1945. For this series, we relied heavily on one source in particular. A book called Their Day in the Sun: Women of the Manhattan Project. It is probably, and I am not exaggerating, the most important work out there on the topic.

And this week, we want to pay tribute to the two women who wrote it, Ruth Howes, whose voice you just heard, and Caroline Herzenberg.

In the early 1990s, Howes, a physicist at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana, and Herzenberg, also a physicist working at Argonne National Laboratory in Chicago, were asked to contribute to a book on women and the use of military force. Their chapter was called Women in Weapons Development: the Manhattan Project. When their colleagues, men we presume, heard about this, they said: That'll be a short chapter. What women? There weren't any.

Howes and Herzenberg weren't so convinced.

While they were working on that chapter, they went to a meeting of the American Physical Society where they bumped into a friend, Melba Phillips, a distinguished physicist who was one of Robert Oppenheimer's first graduate students at UC Berkeley in the 1930s.

Phillips didn't work on the Manhattan Project, but she suggested they talk to Naomi Livesey French, a mathematician whom by the way you heard about a few weeks ago in a previous episode. She was also at that meeting.

The very next morning, Naomi sat down with Ruth for a four hour interview, in the course of which she gave Ruth names and addresses of women who had worked at Los Alamos with her.

Ruth and Caroline then got in touch with those women who had more suggestions. And that was the beginning. They decided to split up the research.

Ruth Howes: Carol did Chicago. She knew people at Argonne. And who had been at the Met Lab in the early days. And so she handled that end of it. I handled Los Alamos and eventually Hanford.

Katie Hafner: In the end, through all this networking, they found some 300 women and did scores of interviews.

In the book, the chapters are organized by different fields: physicists, chemists, mathematicians, biologists, medical researchers, and technicians. An appendix lists the name of every single woman and details what they did. Clearly, there were plenty of women.

For the past three years, we’ve been collecting names for the Lost Women of Science database, and women who worked on the Manhattan Project, thanks to what we found in Their Day in the Sun, have been included from the start. In the spring of 2022, I went to visit Ruth Howes at her home in Santa Fe. She's 78 now. A few days later, we did a formal interview.

Ruth told me she was surprised by the sheer number of women they uncovered. On top of the dozens and dozens of scientists with advanced degrees, Ruth said.

Ruth Howes: If you count the women who ran the calculators at Los Alamos and the technicians at Chicago, you get huge numbers.

Katie Hafner: But in reports written after the war, the women's contributions were routinely missing.

Ruth Howes: And most of the formal histories of the project ignore the women entirely.

Katie Hafner: Why do you think they ignore the women?

Ruth Howes: Because they didn't consider physics a woman's field.

Katie Hafner: But the women were there in plain sight doing the work. So why did they ignore the women?

Ruth Howes: Goodness knows, women are not scientists. You should know that by now.

Katie Hafner: Their Day in the Sun lays that myth to rest. It lists woman after woman and their contributions, and the sheer amount of work Ruth and Caroline put into it shines through.

Karen Herzenberg: I know they spent 10 years on it.

Katie Hafner: That's Karen Herzenberg, Caroline's daughter. Caroline is 92 now. When I talked to Karen recently, she said she remembered when her mother was working on the book.

Karen Herzenberg: Mom immediately gave me a copy as soon as it came out. I believe she gave them to all of us on Christmas, the year that they were published.

Katie Hafner: That was 1999. The book got some nice reviews. Library Journal recommended it for libraries’ history of science collections. And one review praised it as a work of “empowerment” for women and girls considering careers in science. Now, two decades later, even Ruth uses the book as a reference.

Ruth Howes: I've now forgotten. Most of what I knew when I was younger.

Katie Hafner: So when she needs to refresh her memory, she goes to the book. This, of course, triggered a thought. Could we preserve all the documents their research generated? The interview transcripts, the letters they received, the letters they wrote, the notes they took. I could already see the Lost Women of Science team descending on Ruth's house in Santa Fe, scanners in hand, to make copies of everything she had and adding it to our Lost Women of Science Archive.

But then... I asked her this.

Katie Hafner: Did you keep all your papers?

Ruth Howes: No, not all of them. Some of them.

Katie Hafner: Did you keep any of the interviews, transcripts?

Ruth Howes: No. Oh, I don't think I did.

Katie Hafner: Oh, that is just devastating to hear.

Ruth Howes: I'm sorry. I didn't know that anybody would be interested in them.

Katie Hafner: So do you think they ended up in a recycling bin?

Ruth Howes: Yes.

Katie Hafner: I asked the same question of Caroline Herzenberg's daughter, Karen.

Karen Herzenberg: No. Um, I, I haven't seen anything and I've been through a lot of papers on the last few years, so, unfortunately, unfortunately no.

Katie Hafner: It is indeed a tragedy, because the details that are in the book make you really want to know more. In Their Day in the Sun, Ruth and Caroline remark that of the 300 women they tracked down, half were dead. Don't forget, that was 1999. I'm no actuarial expert, but it's my guess that since then, all of those women have died. All we have, for the most part, is this one slim but invaluable resource.

Katie Hafner: So when you were writing the book, what was your hope? did you hope you would achieve by bringing these women to light?

Ruth Howes: Just that we'd make sure they were not lost. So we wrote the book to tell their stories, and that was our hope, as I remember it.

Katie Hafner: After the film Oppenheimer came out earlier this summer, articles started appearing about the absence of women in the movie. And a lot of those stories cited, you guessed it, Their Day in the Sun. So the book is having a bit of a revival.

Karen Herzenberg said she thinks her mother would appreciate the attention the book has been receiving since the movie came out.

Karen Herzenberg: I think she would be happy about it. I think she would appreciate it.

Katie Hafner: And Ruth says she still gets royalty checks from Temple University Press, the publisher. That doesn't mean the book is super easy to get a hold of. Temple University Press sells it on its website. There are copies on Amazon but delivery takes a month, and you can borrow it, at least for now, from archive.org. When I went to visit Ruth in Santa Fe a year ago, I took my copy for her to sign.

Katie Hafner: It wasn't easy to find. In fact, I had to buy it from Abe Books or something. And it is from the Hicksville, New York library.

Ruth Howes: Exactly. And you never would've found it if we hadn't written it.

Katie Hafner: Throughout this series, we've been reading aloud the names of women who worked on the Manhattan Project. We got the list from the back of Ruth and Caroline's book. And when we interviewed Ruth last year, it dawned on me that reading the names aloud might be a good idea. All the names. So Ruth and producer Nora Mathison and I took turns reading them.

Since then, we've recruited a dozen or so additional readers of the names. But today, I want to leave you with the voice of just one, Ruth Howes.

Ruth Howes: Helen Arson. Mary Dailey. Margaret Jane Nickson. Emily Leyshon. Ellen Weaver. Patricia Walsh. Lorraine Heller. Priscilla Duffield.

Katie Hafner: This has been Lost Women of the Manhattan Project, a special series from Lost Women of Science. This episode was produced by me, Katie Hafner, with help from Deborah Unger. Lizzy Younan composes our music. Paula Mangin creates our art, Alex Sugiura is our audio engineer, and Danya Abdelhameid is our fact checker.

Thanks too to Amy Scharf, Nora Mathison, Jeff DelViscio, Eowyn Burtner, Lauren Croop, Carla Sephton, and Sophia Levin. We're funded in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and Schmidt Futures. We're distributed by PRX and produced in partnership with Scientific American. You can find a lot more, including the all important donate button at lostwomenofscience.org.

Starting next week, we're bringing you a two-parter, a fresh look at the physicist Lise Meitner through her correspondence with Otto Hahn.

He won the Nobel Prize. She didn't. We will be talking about what those letters reveal about the who, what, where, when and how of the discovery of nuclear fission. See you next week.

Ruth Howes: Rosie Hunter, Reba Holmberg, Mary Newman, Josephine Hinch, Gertrude Nordheim.

Further reading:

Their Day in the Sun: Women of the Manhattan Project, Ruth H. Howes & Caroline L. Herzenberg. Temple University Press, 1999. Paperback 2003.

https://tupress.temple.edu/books/their-day-in-the-sun

Physics Today: Review of Their Day in the Sun: Women of the Manhattan Project, Ruth H. Howes & Caroline L. Herzenberg, Volume 53, Issue 7, July 2000.

https://pubs.aip.org/physicstoday/article/53/7/59/411394/Their-Day-in-the-Sun-Women-of-the-Manhattan

Voices of the Manhattan Project, Ruth Howes’s interview, Atomic Heritage Foundation, October 12, 2016.

https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/voices/oral-histories/ruth-howess-interview

[Image credit: Paula Mangin]