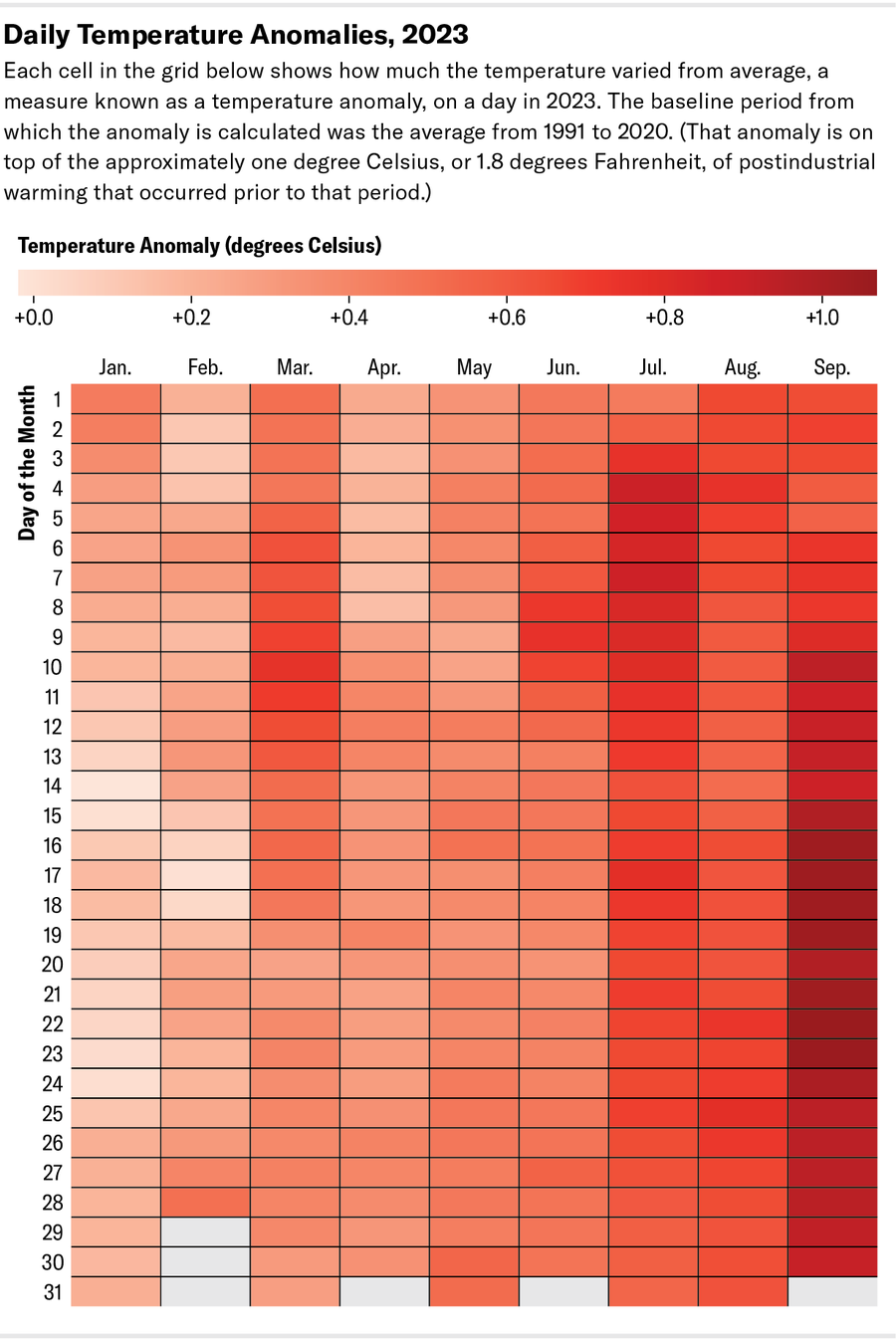

In a year already overloaded with so many climate-related superlatives, it’s time to add another to the list: September was the most anomalously warm month ever recorded.

And the steady heat building this year could make 2023 not only the hottest year on record but the first to exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial temperatures, or the stable climate that preceded the massive release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere from burning fossil fuels. Under the landmark Paris climate accord, nations have pledged to try to keep global warming under that threshold. “It’s very worrying,” says Kate Marvel, a senior climate scientist at Project Drawdown, a nonprofit organization that develops roadmaps for climate solutions.

According to data kept by the Japan Meteorological Agency, this September was about 0.5 degree C (0.9 degree F) hotter than the previous hottest September in 2020. It was also about 0.2 degree C (0.4 degree F) warmer than the previous record high temperature anomaly—a measure of how much warmer or colder a given time period is, compared with the average—which had been set in February 2016 during a blockbuster El Niño.

The September anomaly “is so far above anything we’ve seen before,” says Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist who works at the payment processing firm Stripe and wrote about September’s heat in a recent blog post. On X, formerly known as Twitter, he called the feat “absolutely gobsmackingly bananas.”

The milestone reached last month comes on the heels of July setting the record for the hottest month overall. (July is always the hottest month of the year globally because it occurs at the peak of the Northern Hemisphere summer. The Northern Hemisphere has much more landmass to soak up the sun’s rays than the Southern Hemisphere, so it has the bigger influence on the global annual temperature cycle.)

In a marker of just how much global temperatures have risen in recent decades, Hausfather observes, “this September will be hotter than most Julys before the last decade or two.”

Two main factors are at play in driving temperatures to such extremes: their inexorable increase from burning fossil fuels and an El Niño event that is shaping up to be a strong one. El Niño is a part of a natural climate cycle that features a tongue of unusually warm waters across the eastern Pacific Ocean. Those waters release heat into the atmosphere and can cause a cascade of changes to key atmospheric circulation patterns linked to the weather around the world.

Heat waves have broken records all over the globe during the past few months, including prolonged events called heat domes that plagued the southern stretch of the U.S. and parts of the Mediterranean. Summerlike temperatures were even felt in South America during the Southern Hemisphere’s winter. Two of the heat waves—one in the U.S. Southwest and one in Europe—were found to be virtually impossible without global warming. And summerlike heat has continued in places into October.

The most drastic temperature anomalies typically come in the winter months, when El Niño peaks in strength. In fact, the previous most anomalously warm month was February 2016, during one of the strongest El Niños on record. But this year “we’re seeing these [big anomalies] in the Northern Hemisphere summer,” Hausfather says. That leaves open the possibility of even larger anomalies when this event peaks this winter, particularly if it ends up being another strong event.

It is possible there is also some influence from the phasing out of sulfur-containing fuels used by ships because the aerosols spewed into the air from burning those fuels tend to have a slight cooling effect. The eruption of the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai volcano in the southern Pacific Ocean last year may also be nudging up temperatures because of the huge amounts of water vapor—also a greenhouse gas—it injected into the atmosphere. But both factors have very small influences, compared with climate change and El Niño.

Given that this El Niño is expected to persist and likely to strengthen, there’s a good chance that 2023 or 2024—or both—will become the hottest year on record, besting 2016 (and 2020, which some agencies who monitor climate have tied with 2016). That isn’t surprising, given that there has been a tenth of a degree of warming since 2016, though it is “remarkable just how quickly we’ve seen warmth this year,” Hausfather says. Part of the apparent rapid warming is because 2023 began in the tail end of an unusual string of three back-to-back La Niña events. These tend to have a cooling impact on the global climate, though La Niñas today are hotter than even El Niños of several decades ago.

Beyond potentially becoming the hottest year on record, 2023 could also be the first year to top 1.5 degrees C above preindustrial temperatures (some individual months have already passed that threshold). But even if that happens, all hope is not lost for meeting the Paris accord goals. That threshold is measured as an average of several decades, and climate scientists have long expected that a single year would pass that mark a decade or so before the world could be considered permanently above that limit. “There is still time to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees,” Marvel says. “It is going to be incredibly difficult. The pathways are narrowing.”

But this year should be considered a warning of the future we face if we don’t take rapid, ambitious action. “This is what the world looks like when it’s 1.5 degrees hotter in a year, and it’s terrible,” she says. When the world does permanently pass 1.5 degrees C, the climate anomalies for individual years will reach higher than that mark.

To stave off that future, every bit of carbon we can keep, or take, out of the atmosphere is crucial. “Every tenth of a degree matters,” Hausfather says.