After several tense days of earthquake swarms, people living on Iceland’s Reykjanes Peninsula are in limbo as they wait to see whether a surging blob of magma about half a mile (nearly a kilometer) beneath their feet will gently quiet down—or explode in a damaging volcanic eruption.

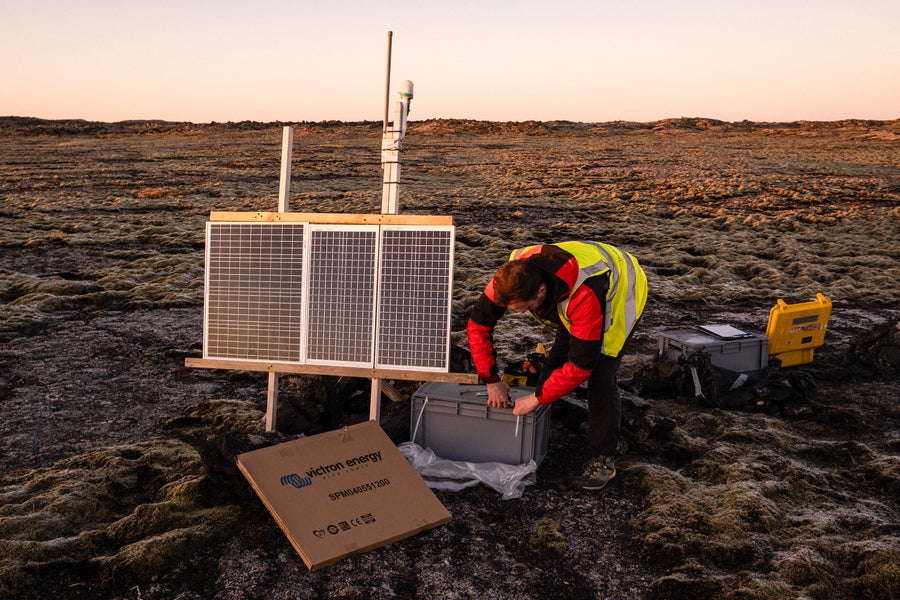

More than 3,000 people been evacuated from the town of Grindavík in southwestern Iceland, which has been damaged by days of relentless quakes. Some of these have opened fissures in the landscape, including across roads. Seismic activity had quieted as of November 14, geoscientists say, but it’s hard to tell whether this is a lasting trend or the calm before the storm. Previous eruptions in the region had shown patterns of quiet just before the lava started flowing. “We don’t know yet if [the volcano] will erupt,” says Vincent Drouin, a staff scientist at the Icelandic Meteorological Office (IMO), who specializes in monitoring the landscape. “We’re trying to look for small signs.”

The Reykjanes Peninsula is home to the famous Blue Lagoon hot spring, which regularly draws tourists from around the world and is now closed because of the danger. The region’s geology has been restless for several weeks, Drouin says, with seismic monitors and GPS stations showing the ground inflating—a sign of magma movement below. And last week, earthquake activity started kicking up in a big way. On November 9, for example, the IMO reported that about 1,400 earthquakes were recorded within 24 hours. The largest was magnitude 4.8. Then, on the following afternoon, a relentless swarm of strong quakes shook the peninsula. “This was incredible,” says Dave McGarvie, a volcanologist at Lancaster University in England, who studies Icelandic eruptions. “I don’t think I’ve seen anything like this in Iceland before.”

The reason for the temblors was a massive underground river of magma that rapidly shot out from a temporary reservoir called a “sill,” where it had been accumulating about 2.5 miles (4 km) down. As it surged out of the sill, it formed a 9.3-mile-long (15-km-long) intrusion, or dyke. This dyke now sits about 0.5 mile (800 meters) below the surface, according to the IMO. If there is an eruption, it will probably occur somewhere along the dyke.

“What surprised people here is the speed of things happening,” says Sigrún Hreinsdóttir, a senior geodetic scientist at GNS Science in New Zealand, who has studied the region of the Reykjanes Peninsula. Some seismic stations in the area showed the ground subsiding more than three feet (1 m) in a matter of hours as the magma moved, she says.

Authorities declared a state of emergency and ordered the evacuation of Grindavík on Friday night. By Tuesday, Drouin says, seismic activity had slowed slightly, yet the IMO has still detected more than 700 small earthquakes along the intrusion since midnight local time.

The peninsula’s geology is contributing to the size of some of those quakes, Hreinsdóttir says. Iceland sits over a volcanic hotspot, where magma comes close to the surface. The island nation is also right on top of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the boundary where the North American and Eurasian plates are slowly pulling away from each other. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is mostly underwater but comes onshore on the heel of the Reykjanes Peninsula. “We have both a seismic zone and volcanic systems,” Hreinsdóttir says.

She explains that although the movement of the magma itself makes the ground shudder, the subterranean changes wrought by this movement also change the stress on various faults in this seismically active region. Thus, the magma activity is triggering earthquakes on nearby faults, and these quakes are larger than those caused directly by magma movement alone.

Given the region’s wild geology, perhaps it’s not surprising that this is not the first time the Reykjanes Peninsula has rumbled to life. Every 1,000 years or so the area goes through periods of volcanic activity that each last 200 or 300 years, Hreinsdóttir says. The last time that happened was between the 10th and 13th centuries. Not many records survive from that time, so it’s hard to use that event to predict what will happen in the future.

“Each time you make a new eruption, you make new magma; you change the systems,” Drouin says. “So it will not be the same as last time.”

Hreinsdóttir says that it does seem that a new period of volcanic activity is dawning, however. In 2021 other volcanic systems on the peninsula produced four magma intrusions. Three of those ended in eruptions, albeit small ones in unpopulated areas.

If the latest unrest does lead to an eruption, it will not be likely to lead to the widespread airline cancellations that occurred in 2010 when the Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajökull erupted. That volcano pumped volcanic ash more than 5.6 miles (9 km) into the atmosphere, severely disrupting flights over the North Atlantic. The volcanic systems on Reykjanes tend to produce oozy, low-gas lava flows with very little ash. The biggest danger is probably that lava flows will threaten Grindavík or the Reykjanes Power Station, a geothermal plant nearby. Authorities may dig trenches or earthen dams to redirect any flows away from these areas in the event of an eruption, Drouin says.

“Every day we try to reassess, based on the data we have, to see if the dyke is inflating and where,” Drouin says. “That’s probably where it is most likely to erupt.”