A Bald Eagle disappeared into the trees on the far bank of the Tennessee River just as the two researchers at the bow of our modest motorboat began hauling in the trawl net. Eagles have rebounded so well that it's unusual not to see one here these days, Warren Stiles of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service told me as the net got closer. On an almost cloudless spring morning in the 50th year of the Endangered Species Act, only a third of a mile downstream from the Tennessee Valley Authority's big Nickajack Dam, we were searching for one of the ESA's more notorious beneficiaries: the Snail Darter. A few months earlier Stiles and the FWS had decided that, like the Bald Eagle, the little fish no longer belonged on the ESA's endangered species list. We were hoping to catch the first nonendangered specimen.

Dave Matthews, a TVA biologist, helped Stiles empty the trawl. Bits of wood and rock spilled onto the deck, along with a Common Logperch maybe six inches long. So did an even smaller fish; a hair over two inches, it had alternating vertical bands of dark and light brown, each flecked with the other color, a pattern that would have made it hard to see against the gravelly river bottom. It was a Snail Darter in its second year, Matthews said, not yet full-grown.

Everybody loves a Bald Eagle. There is much less consensus about the Snail Darter. Yet it epitomizes the main controversy still swirling around the ESA, signed into law on December 28, 1973, by President Richard Nixon: Can we save all the obscure species of this world, and should we even try, if they get in the way of human imperatives? The TVA didn't think so in the 1970s, when the plight of the Snail Darter—an early entry on the endangered species list—temporarily stopped the agency from completing a huge dam. When the U.S. attorney general argued the TVA's case before the Supreme Court with the aim of sidestepping the law, he waved a jar that held a dead, preserved Snail Darter in front of the nine judges in black robes, seeking to convey its insignificance.

Now I was looking at a living specimen. It darted around the bottom of a white bucket, bonking its nose against the side and delicately fluttering the translucent fins that swept back toward its tail.

“It's kind of cute,” I said.

Matthews laughed and slapped me on the shoulder. “I like this guy!” he said. “Most people are like, ‘Really? That's it?’ ” He took a picture of the fish and clipped a sliver off its tail fin for DNA analysis but left it otherwise unharmed. Then he had me pour it back into the river. The next trawl, a few miles downstream, brought up seven more specimens.

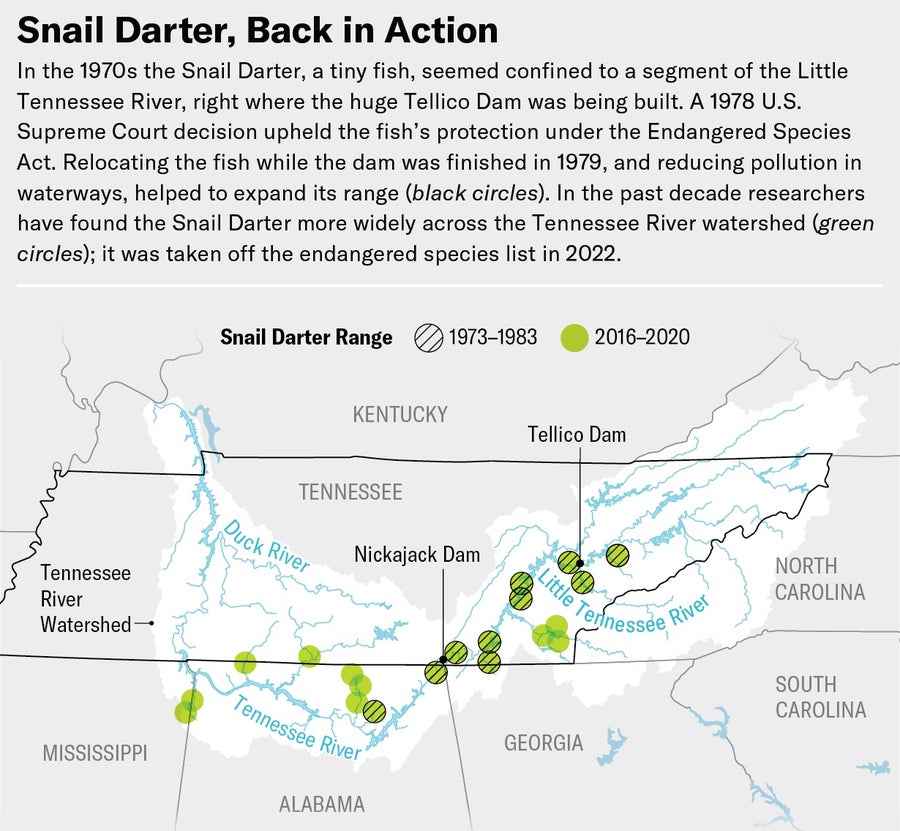

In the late 1970s the Snail Darter seemed confined to a single stretch of a single tributary of the Tennessee River, the Little Tennessee, and to be doomed by the TVA's ill-considered Tellico Dam, which was being built on the tributary. The first step on its twisting path to recovery came in 1978, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, surprisingly, that the ESA gave the darter priority even over an almost finished dam. “It was when the government stood up and said, ‘Every species matters, and we meant it when we said we're going to protect every species under the Endangered Species Act,’” says Tierra Curry, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity.

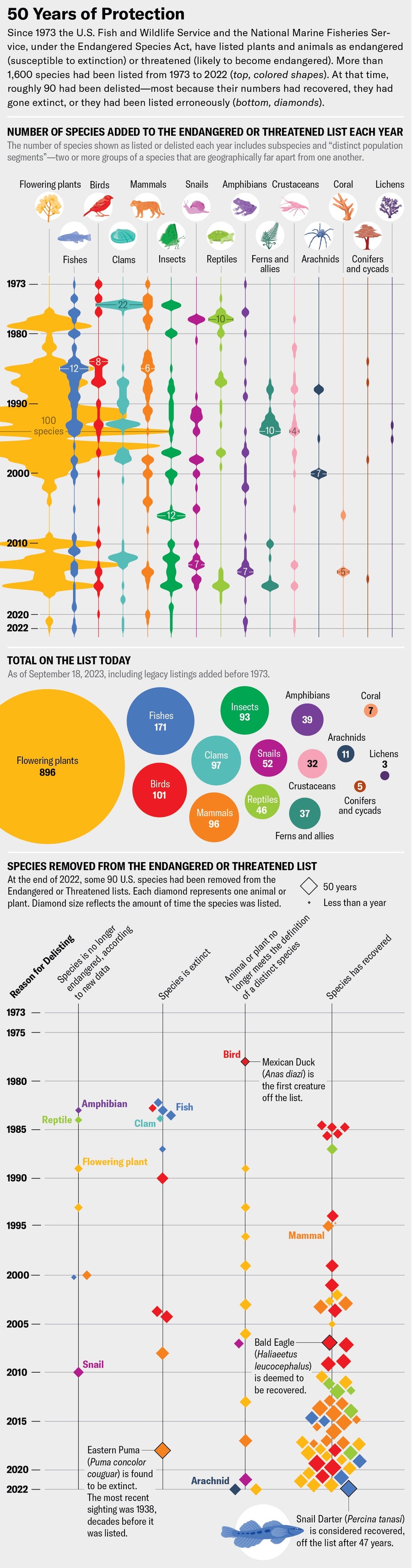

Today the Snail Darter can be found along 400 miles of the river's main stem and multiple tributaries. ESA enforcement has saved dozens of other species from extinction. Bald Eagles, American Alligators and Peregrine Falcons are just a few of the roughly 60 species that had recovered enough to be “delisted” by late 2023.

And yet the U.S., like the planet as a whole, faces a growing biodiversity crisis. Less than 6 percent of the animals and plants ever placed on the list have been delisted; many of the rest have made scant progress toward recovery. What's more, the list is far from complete: roughly a third of all vertebrates and vascular plants in the U.S. are vulnerable to extinction, says Bruce Stein, chief scientist at the National Wildlife Federation. Populations are falling even for species that aren't yet in danger. “There are a third fewer birds flying around now than in the 1970s,” Stein says. We're much less likely to see a White-throated Sparrow or a Red-winged Blackbird, for example, even though neither species is yet endangered.

The U.S. is far emptier of wildlife sights and sounds than it was 50 years ago, primarily because habitat—forests, grasslands, rivers—has been relentlessly appropriated for human purposes. The ESA was never designed to stop that trend, any more than it is equipped to deal with the next massive threat to wildlife: climate change. Nevertheless, its many proponents say, it is a powerful, foresightful law that we could implement more wisely and effectively, perhaps especially to foster stewardship among private landowners. And modest new measures, such as the Recovering America's Wildlife Act—a bill with bipartisan support—could further protect flora and fauna.

That is, if special interests don't flout the law. After the 1978 Supreme Court decision, Congress passed a special exemption to the ESA allowing the TVA to complete the Tellico Dam. The Snail Darter managed to survive because the TVA transplanted some of the fish from the Little Tennessee, because remnant populations turned up elsewhere in the Tennessee Valley, and because local rivers and streams slowly became less polluted following the 1972 Clean Water Act, which helped fish rebound.

Under pressure from people enforcing the ESA, the TVA also changed the way it managed its dams throughout the valley. It started aerating the depths of its reservoirs, in some places by injecting oxygen. It began releasing water from the dams more regularly to maintain a minimum flow that sweeps silt off the river bottom, exposing the clean gravel that Snail Darters need to lay their eggs and feed on snails. The river system “is acting more like a real river,” Matthews says. Basically, the TVA started considering the needs of wildlife, which is really what the ESA requires. “The Endangered Species Act works,” Matthews says. “With just a little bit of help, [wildlife] can recover.”

The trouble is that many animals and plants aren't getting that help—because government resources are too limited, because private landowners are alienated by the ESA instead of engaged with it, and because as a nation the U.S. has never fully committed to the ESA's essence. Instead, for half a century, the law has been one more thing that polarizes people's thinking.

It may seem impossible today to imagine the political consensus that prevailed on environmental matters in 1973. The U.S. Senate approved the ESA unanimously, and the House passed it by a vote of 390 to 12. “Some people have referred to it as almost a statement of religion coming out of the Congress,” says Gary Frazer, who as assistant director for ecological services at the FWS has been overseeing the act's implementation for nearly 25 years.

But loss of faith began five years later with the Snail Darter case. Congresspeople who had been thinking of eagles, bears and Whooping Cranes when they passed the ESA, and had not fully appreciated the reach of the sweeping language they had approved, were disabused by the Supreme Court. It found that the legislation had created, “wisely or not ... an absolute duty to preserve all endangered species,” Chief Justice Warren E. Burger said after the Snail Darter case concluded. Even a recently discovered tiny fish had to be saved, “whatever the cost,” he wrote in the decision.

Was that wise? For both environmentalists such as Curry and many nonenvironmentalists, the answer has always been absolutely. The ESA “is the basic Bill of Rights for species other than ourselves,” says National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore, who is building a “photo ark” of every animal visible to the naked eye as a record against extinction. (He has taken studio portraits of 15,000 species so far.) But to critics, the Snail Darter decision always defied common sense. They thought it was “crazy,” says Michael Bean, a leading ESA expert, now retired from the Environmental Defense Fund. “That dichotomy of view has remained with us for the past 45 years.”

According to veteran Washington, D.C., environmental attorney Lowell E. Baier, author of a new history called The Codex of the Endangered Species Act, both the act itself and its early implementation reflected a top-down, federal “command-and-control mentality” that still breeds resentment. FWS field agents in the early days often saw themselves as combat biologists enforcing the act's prohibitions. After the Northern Spotted Owl's listing got tangled up in a bitter 1990s conflict over logging of old-growth forests in the Pacific Northwest, the FWS became more flexible in working out arrangements. “But the dark mythology of the first 20 years continues in the minds of much of America,” Baier says.

The law can impose real burdens on landowners. Before doing anything that might “harass” or “harm” an endangered species, including modifying its habitat, they need to get a permit from the FWS and present a “habitat conservation plan.” Prosecutions aren't common, because evidence can be elusive, but what Bean calls “the cloud of uncertainty” surrounding what landowners can and cannot do can be distressing.

Requirements the ESA places on federal agencies such as the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management—or on the TVA—can have large economic impacts. Section 7 of the act prohibits agencies from taking, permitting or funding any action that is likely to “jeopardize the continued existence” of a listed species. If jeopardy seems possible, the agency must consult with the FWS first (or the National Marine Fisheries Service for marine species) and seek alternative plans.

“When people talk about how the ESA stops projects, they've been talking about section 7,” says conservation biologist Jacob Malcom. The Northern Spotted Owl is a strong example: an economic analysis suggests the logging restrictions eliminated thousands of timber-industry jobs, fueling conservative arguments that the ESA harms humans and economic growth.

In recent decades, however, that view has been based “on anecdote, not evidence,” Malcom claims. At Defenders of Wildlife, where he worked until 2022 (he's now at the U.S. Department of the Interior), he and his colleagues analyzed 88,290 consultations between the FWS and other agencies from 2008 to 2015. “Zero projects were stopped,” Malcom says. His group also found that federal agencies were only rarely taking the active measures to recover a species that section 7 requires—like what the TVA did for the Snail Darter. For many listed species, the FWS does not even have recovery plans.

Endangered species also might not recover because “most species are not receiving protection until they have reached dangerously low population sizes,” according to a 2022 study by Erich K. Eberhard of Columbia University and his colleagues. Most listings occur only after the FWS has been petitioned or sued by an environmental group—often the Center for Biological Diversity, which claims credit for 742 listings. Years may go by between petition and listing, during which time the species' population dwindles. Noah Greenwald, the center's endangered species director, thinks the FWS avoids listings to avoid controversy—that it has internalized opposition to the ESA.

He and other experts also say that work regarding endangered species is drastically underfunded. As more species are listed, the funding per species declines. “Congress hasn't come to grips with the biodiversity crisis,” says Baier, who lobbies lawmakers regularly. “When you talk to them about biodiversity, their eyes glaze over.” Just this year federal lawmakers enacted a special provision exempting the Mountain Valley Pipeline from the ESA and other challenges, much as Congress had exempted the Tellico Dam. Environmentalists say the gas pipeline, running from West Virginia to Virginia, threatens the Candy Darter, a colorful small fish. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 provided a rare bit of good news: it granted the FWS $62.5 million to hire more biologists to prepare recovery plans.

The ESA is often likened to an emergency room for species: overcrowded and understaffed, it has somehow managed to keep patients alive, but it doesn't do much more. The law contains no mandate to restore ecosystems to health even though it recognizes such work as essential for thriving wildlife. “Its goal is to make things better, but its tools are designed to keep things from getting worse,” Bean says. Its ability to do even that will be severely tested in coming decades by threats it was never designed to confront.

The ESA requires a species to be listed as “threatened” if it might be in danger of extinction in the “foreseeable future.” The foreseeable future will be warmer. Rising average temperatures are a problem, but higher heat extremes are a bigger threat, according to a 2020 study.

Scientists have named climate change as the main cause of only a few extinctions worldwide. But experts expect that number to surge. Climate change has been “a factor in almost every species we've listed in at least the past 15 years,” Frazer says. Yet scientists struggle to forecast whether individual species can “persist in place or shift in space”—as Stein and his co-authors put it in a recent paper—or will be unable to adapt at all and will go extinct. On June 30 the FWS issued a new rule that will make it easier to move species outside their historical range—a practice it once forbade except in extreme circumstances.

Eventually, though, “climate change is going to swamp the ESA,” says J. B. Ruhl, a law professor at Vanderbilt University, who has been writing about the problem for decades. “As more and more species are threatened, I don't know what the agency does with that.” To offer a practical answer, in a 2008 paper he urged the FWS to aggressively identify the species most at risk and not waste resources on ones that seem sure to expire.

Yet when I asked Frazer which urgent issues were commanding his attention right now, his first thought wasn't climate; it was renewable energy. “Renewable energy is going to leave a big footprint on the planet and on our country,” he says, some of it threatening plants and animals if not implemented well. “The Inflation Reduction Act is going to lead to an explosion of more wind and solar across the landscape.

Long before President Joe Biden signed that landmark law, conflicts were proliferating: Desert Tortoise versus solar farms in the Mojave Desert, Golden Eagles versus wind farms in Wyoming, Tiehm's Buckwheat (a little desert flower) versus lithium mining in Nevada. The mine case is a close parallel to that of Snail Darters versus the Tellico Dam. The flower, listed as endangered just last year, grows on only a few acres of mountainside in western Nevada, right where a mining company wants to extract lithium. The Center for Biological Diversity has led the fight to save it. Elsewhere in Nevada people have used the ESA to stop, for the moment, a proposed geothermal plant that might threaten the two-inch Dixie Valley Toad, discovered in 2017 and also declared endangered last year.

Does an absolute duty to preserve all endangered species make sense in such places? In a recent essay entitled “A Time for Triage,” Columbia law professor Michael Gerrard argues that “the environmental community has trade-off denial. We don't recognize that it's too late to preserve everything we consider precious.” In his view, given the urgency of building the infrastructure to fight climate change, we need to be willing to let a species go after we've done our best to save it. Environmental lawyers adept at challenging fossil-fuel projects, using the ESA and other statutes, should consider holding their fire against renewable installations. “Just because you have bullets doesn't mean you shoot them in every direction,” Gerrard says. “You pick your targets.” In the long run, he and others argue, climate change poses a bigger threat to wildlife than wind turbines and solar farms do.

For now habitat loss remains the overwhelming threat. What's truly needed to preserve the U.S.'s wondrous biodiversity, both Stein and Ruhl say, is a national network of conserved ecosystems. That won't be built with our present politics. But two more practical initiatives might help.

The first is the Recovering America's Wildlife Act, which narrowly missed passage in 2022 and has been reintroduced this year. It builds on the success of the 1937 Pittman-Robertson Act, which funds state wildlife agencies through a federal excise tax on guns and ammunition. That law was adopted to address a decline in game species that had hunters alarmed. The state refuges and other programs it funded are why deer, ducks and Wild Turkeys are no longer scarce.

The recovery act would provide $1.3 billion a year to states and nearly $100 million to Native American tribes to conserve nongame species. It has bipartisan support, in part, Stein says, because it would help arrest the decline of a species before the ESA's “regulatory hammer” falls. Although it would be a large boost to state wildlife budgets, the funding would be a rounding error in federal spending. But last year Congress couldn't agree on how to pay for the measure. Passage “would be a really big deal for nature,” Curry says.

The second initiative that could promote species conservation is already underway: bringing landowners into the fold. Most wildlife habitat east of the Rocky Mountains is on private land. That's also where habitat loss is happening fastest. Some experts say conservation isn't likely to succeed unless the FWS works more collaboratively with landowners, adding carrots to the ESA's regulatory stick. Bean has long promoted the idea, including when he worked at the Interior Department from 2009 to early 2017. The approach started, he says, with the Red-cockaded Woodpecker.

When the ESA was passed, there were fewer than 10,000 Red-cockaded Woodpeckers left of the millions that had once lived in the Southeast. Humans had cut down the old pine trees, chiefly Longleaf Pine, that the birds excavate cavities in for roosting and nesting. An appropriate tree has to be large, at least 60 to 80 years old, and there aren't many like that left. The longleaf forest, which once carpeted up to 90 million acres from Virginia to Texas, has been reduced to less than three million acres of fragments.

In the 1980s the ESA wasn't helping because it provided little incentive to preserve forest on private land. In fact, Bean says, it did the opposite: landowners would sometimes clear-cut potential woodpecker habitat just to avoid the law's constraints. The woodpecker population continued to drop until the 1990s. That's when Bean and his Environmental Defense Fund colleagues persuaded the FWS to adopt “safe-harbor agreements” as a simple solution. An agreement promised landowners that if they let pines grow older or took other woodpecker-friendly measures, they wouldn't be punished; they remained free to decide later to cut the forest back to the baseline condition it had been in when the agreement was signed.

That modest carrot was inducement enough to quiet the chainsaws in some places. “The downward trends have been reversed,” Bean says. “In places like South Carolina, where they have literally hundreds of thousands of acres of privately owned forest enrolled, Red-cockaded Woodpecker numbers have shot up dramatically.”

The woodpecker is still endangered. It still needs help. Because there aren't enough old pines, land managers are inserting lined, artificial cavities into younger trees and sometimes moving birds into them to expand the population. They are also using prescribed fires or power tools to keep the longleaf understory open and grassy, the way fires set by lightning or Indigenous people once kept it and the way the woodpeckers like it. Most of this work is taking place, and most Red-cockaded Woodpeckers are still living, on state or federal land such as military bases. But a lot more longleaf must be restored to get the birds delisted, which means collaborating with private landowners, who own 80 percent of the habitat.

Leo Miranda-Castro, who retired last December as director of the FWS's southeast region, says the collaborative approach took hold at regional headquarters in Atlanta in 2010. The Center for Biological Diversity had dropped a “mega petition” demanding that the FWS consider 404 new species for listing. The volume would have been “overwhelming,” Miranda-Castro says. “That's when we decided, ‘Hey, we cannot do this in the traditional way.’ The fear of listing so many species was a catalyst” to look for cases where conservation work might make a listing unnecessary.

An agreement affecting the Gopher Tortoise shows what is possible. Like the woodpeckers, it is adapted to open-canopied longleaf forests, where it basks in the sun, feeds on herbaceous plants and digs deep burrows in the sandy soil. The tortoise is a keystone species: more than 300 other animals, including snakes, foxes and skunks, shelter in its burrows. But its numbers have been declining for decades.

Urbanization is the main threat to the tortoises, but timberland can be managed in a way that leaves room for them. Eager to keep the species off the list, timber companies, which own 20 million acres in its range, agreed to figure out how to do that—above all by returning fire to the landscape and keeping the canopy open. One timber company, Resource Management Service, said it would restore Longleaf Pine on about 3,700 acres in the Florida panhandle, perhaps expanding to 200,000 acres eventually. It even offered to bring other endangered species onto its land, which delighted Miranda-Castro: “I had never heard about that happening before.” Last fall the FWS announced that the tortoise didn't need to be listed in most of its range.

Miranda-Castro now directs Conservation Without Conflict, an organization that seeks to foster conversation and negotiation in settings where the ESA has more often generated litigation. “For the first 50 years the stick has been used the most,” Miranda-Castro says. “For the next 50 years we're going to be using the carrots way more.” On his own farm outside Fort Moore, Ga., he grows Longleaf Pine—and Gopher Tortoises are benefiting.

The Center for Biological Diversity doubts that carrots alone will save the reptile. It points out that the FWS's own models show small subpopulations vanishing over the next few decades and the total population falling by nearly a third. In August 2023 it filed suit against the FWS, demanding the Gopher Tortoise be listed.

The FWS itself resorted to the stick this year when it listed the Lesser Prairie-Chicken, a bird whose grassland home in the Southern Plains has long been encroached on by agriculture and the energy industry. The Senate promptly voted to overturn that listing, but President Biden promised to veto that measure if it passes the House.

Behind the debates over strategy lurks the vexing question: Can we save all species? The answer is no. Extinctions will keep happening. In 2021 the FWS proposed to delist 23 more species—not because they had recovered but because they hadn't been seen in decades and were presumed gone. There is a difference, though, between acknowledging the reality of extinction and deliberately deciding to let a species go. Some people are willing to do the latter; others are not. Bean thinks a person's view has a lot to do with how much they've been exposed to wildlife, especially as a child.

Zygmunt Plater, a professor emeritus at Boston College Law School, was the attorney in the 1978 Snail Darter case, fighting for hundreds of farmers whose land would be submerged by the Tellico Dam. At one point in the proceedings Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., asked him, “What purpose is served, if any, by these little darters? Are they used for food?” Plater thinks creatures such as the darter alert us to the threat our actions pose to them and to ourselves. They prompt us to consider alternatives.

The ESA aims to save species, but for that to happen, ecosystems have to be preserved. Protecting the Northern Spotted Owl has saved at least a small fraction of old-growth forest in the Pacific Northwest. Concern about the Red-cockaded Woodpecker and the Gopher Tortoise is aiding the preservation of longleaf forests in the Southeast. The Snail Darter wasn't enough to stop the Tellico Dam, which drowned historic Cherokee sites and 300 farms, mostly for real estate development. But after the controversy, the presence of a couple of endangered mussels did help dissuade the TVA from completing yet another dam, on the Duck River in central Tennessee. That river is now recognized as one of the most biodiverse in North America.

The ESA forced states to take stock of the wildlife they harbored, says Jim Williams, who as a young biologist with the FWS was responsible for listing both the Snail Darter and mussels in the Duck River. Williams grew up in Alabama, where I live. “We didn't know what the hell we had,” he says. “People started looking around and found all sorts of new species.” Many were mussels and little fish. In a 2002 survey, Stein found that Alabama ranked fifth among U.S. states in species diversity. It also ranks second-highest for extinctions; of the 23 extinct species the FWS recently proposed for delisting, eight were mussels, and seven of those were found in Alabama.

One morning this past spring, at a cabin on the banks of Shoal Creek in northern Alabama, I attended a kind of jamboree of local freshwater biologists. At the center of the action, in the shade of a second-floor deck, sat Sartore. He had come to board more species onto his photo ark, and the biologists—most of them from the TVA—were only too glad to help, fanning out to collect critters to be decanted into Sartore's narrow, flood-lit aquarium. He sat hunched before it, a black cloth draped over his head and camera, snapping away like a fashion photographer, occasionally directing whoever was available to prod whatever animal was in the tank into a more artful pose.

As I watched, he photographed a striated darter that didn't yet have a name, a Yellow Bass, an Orangefin Shiner and a giant crayfish discovered in 2011 in the very creek we were at. Sartore's goal is to help people who never meet such creatures feel the weight of extinction—and to have a worthy remembrance of the animals if they do vanish from Earth.

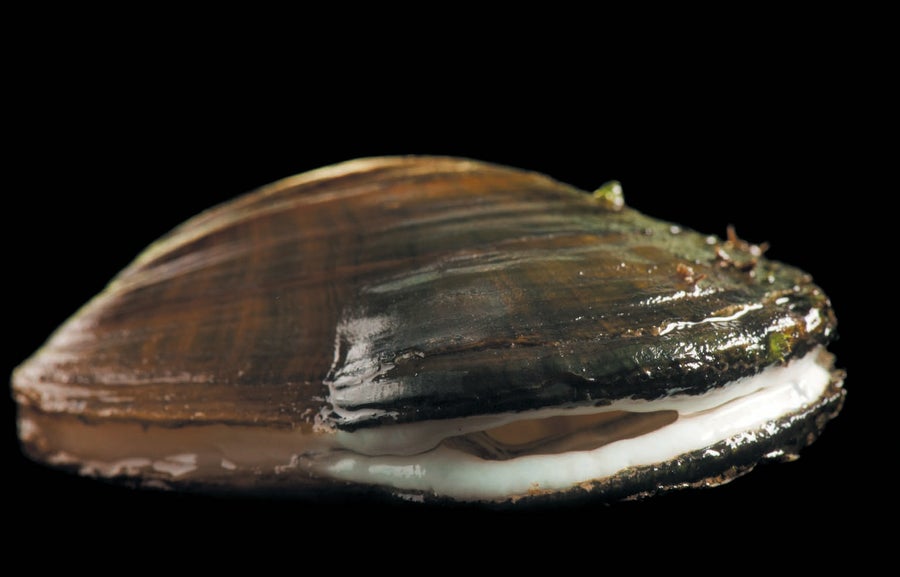

With TVA biologist Todd Amacker, I walked down to the creek and sat on the bank. Amacker is a mussel specialist, following in Williams's footsteps. As his colleagues waded in the shoals with nets, he gave me a quick primer on mussel reproduction. Their peculiar antics made me care even more about their survival.

There are hundreds of freshwater mussel species, Amacker explained, and almost every one tricks a particular species of fish into raising its larvae. The Wavy-rayed Lampmussel, for example, extrudes part of its flesh in the shape of a minnow to lure black bass—and then squirts larvae into the bass's open mouth so they can latch on to its gills and fatten on its blood. Another mussel dangles its larvae at the end of a yard-long fishing line of mucus. The Duck River Darter Snapper—a member of a genus that has already lost most of its species to extinction—lures and then clamps its shell shut on the head of a hapless fish, inoculating it with larvae. “You can't make this up,” Amacker said. Each relationship has evolved over the ages in a particular place.

The small band of biologists who are trying to cultivate the endangered mussels in labs must figure out which fish a particular mussel needs. It's the type of tedious trial-and-error work conservation biologists call “heroic,” the kind that helped to save California Condors and Whooping Cranes. Except these mussels are eyeless, brainless, little brown creatures that few people have ever heard of.

For most mussels, conditions are better now than half a century ago, Amacker said. But some are so rare it's hard to imagine they can be saved. I asked Amacker whether it was worth the effort or whether we just need to accept that we must let some species go. The catch in his voice almost made me regret the question.

“I'm not going to tell you it's not worth the effort,” he said. “It's more that there's no hope for them.” He paused, then collected himself. “Who are we to be the ones responsible for letting a species die?” he went on. “They've been around so long. That's not my answer as a biologist; that's my answer as a human. Who are we to make it happen?”